The Expanded Practice of the Artist’s Book

Immersion in the Artist’s Museum

by Francisco Varela

The essay developed from a residency by Francisco Varela at msdm, the house-studio gallery founded by paula roush, whose artistic practice presents itself as a unique case study of a live–work method. It is its aim to analyse, contextualize and query the principles that guide this method.

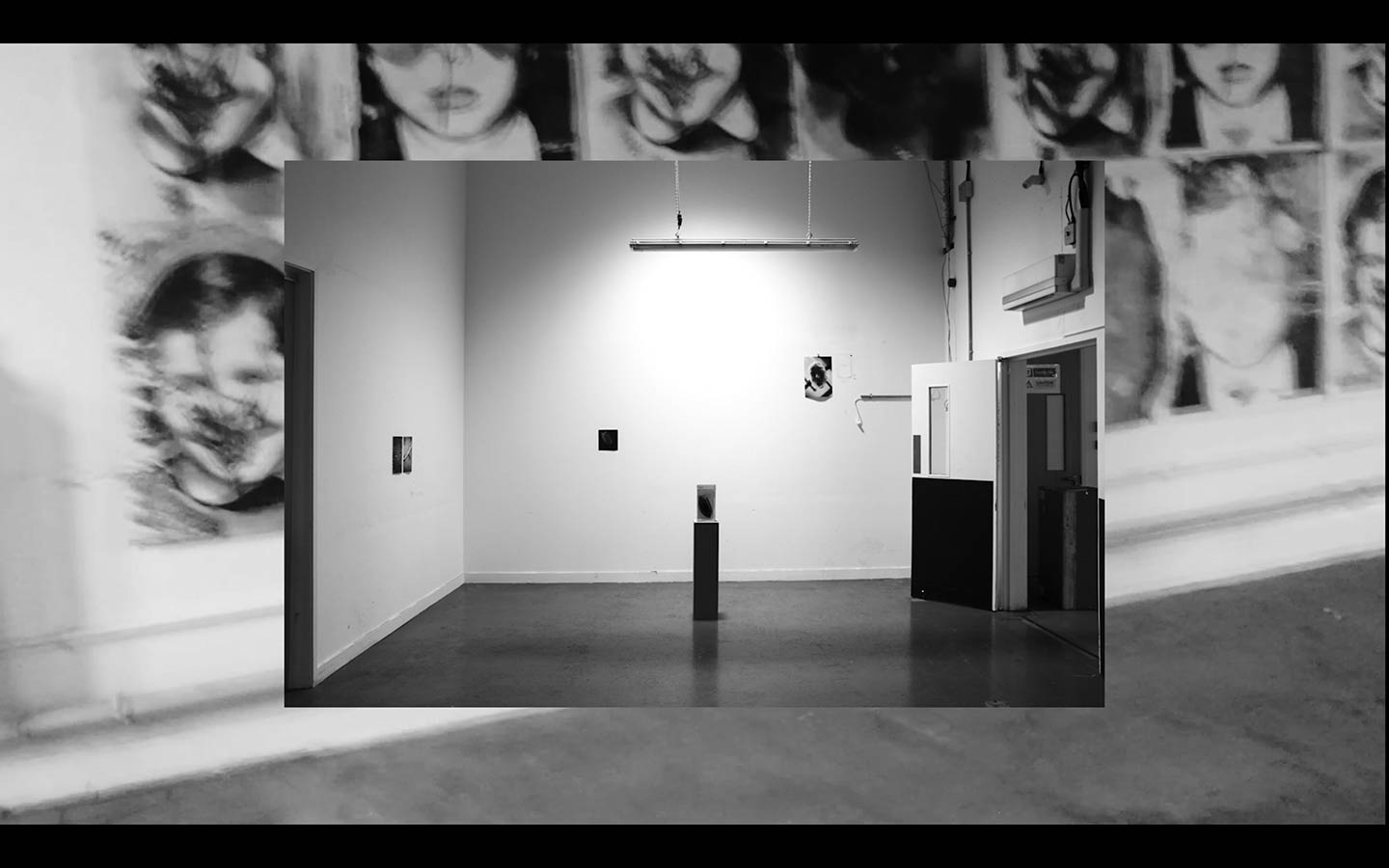

It is an artistic and experiential practice that performs a reinterpretation of the city through collection, research and display of materials as well as an idiosyncratic practice of space making. This is achieved through an immersive practice that results in artefacts and books the artist creates and in the musealisation of the architectural spaces she occupies

First section of the essay explores the “expanded” characteristics of the artist’s book,

probing whether this notion is extensible to the activity of space production practiced

in her house–studio–gallery, an activity which is unique to and inseparable from her

live-work method. These artistic methodologies are clarified within an interdisciplinary

framework that includes the concepts of “autoethnography,” “space–time sequence”

and “contemporaneity.”

Second section explores the notion of “dispositif,” with the intention to reveal the

multiple structuring elements of a live–work practice here called “immersive.”

Third section analyses the “museographic” process inherent to paula’s space, a practice

associated to the house–studio–gallery. This live–work–curation method is identified in

relation to various museological frameworks that are exercised in that space.

Peer Review:

This essay has been peer reviewed through the double-blind process of AMPS (Architecture, Media, Politics, Society), for the conference Connections: Exploring Heritage, Architecture, Cities, Art, Media.

For the video-essay see here

THE EXPANDED PRACTICE OF THE ARTIST’S BOOK

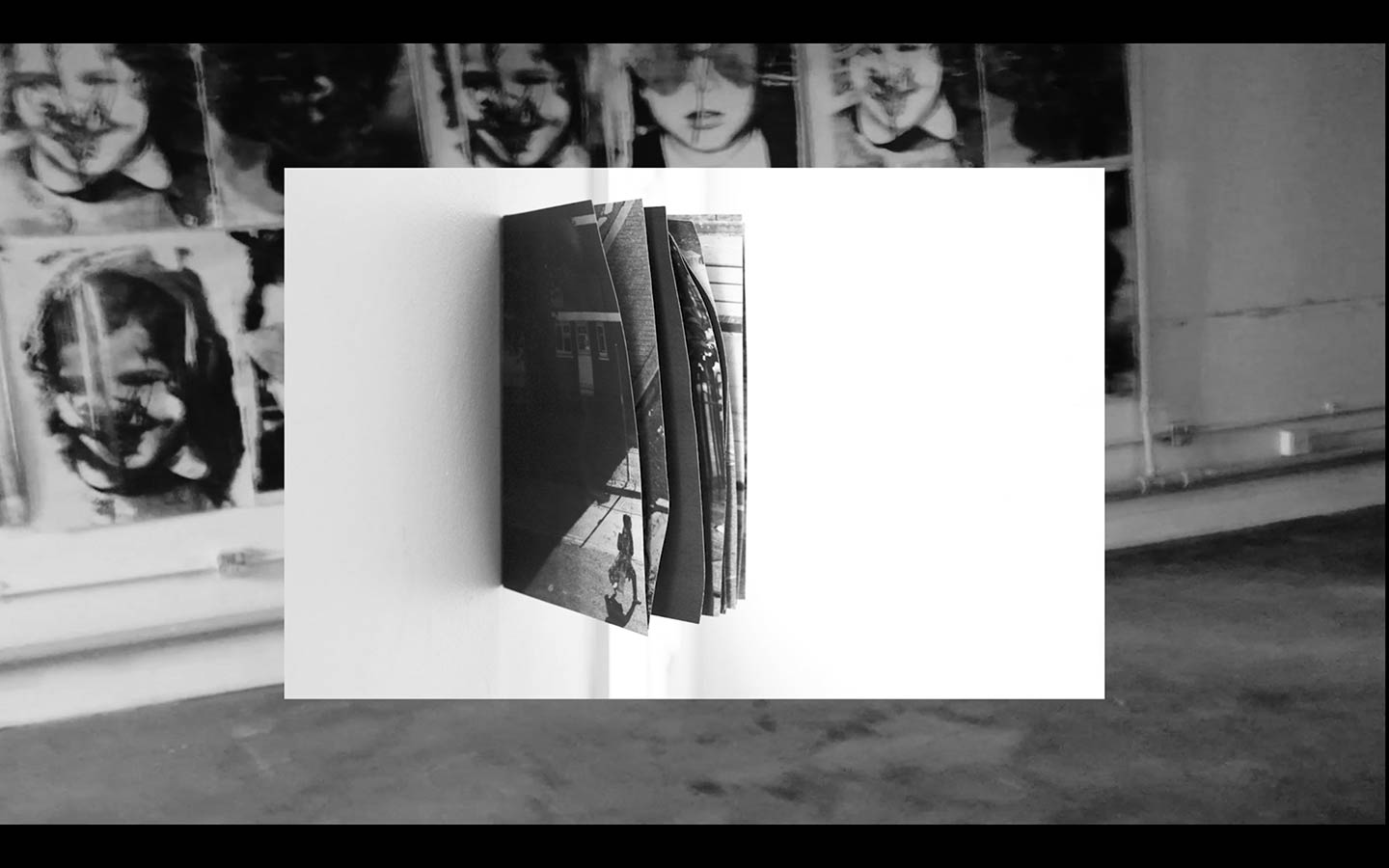

In this text I reflect on paula’s artistic practice. It is a photographic practice and takes place in different formats (or mediums), including installation and publishing. For the past five years, paula has been developing this practice in spaces that are simultaneously home, studio and gallery. It is pertinent to reflect on this live-work method as it is a singular artistic activity, articulated in a unique way with the making of artist’s books (which interests me particularly, since I am also a “maker” of artist’s books). My intention with this reflection is to contribute to an understanding of the unique characteristics of the artist ‘s book practice. I am interested in the ways paula’s artwork is in its totality anchored in an expanded practice of the artist’s book.

These are my initial questions:

Is it possible that the installations (artistic modalities / types of work) produced

in these spaces are also books?

How does the spatialisation of the book’s components expand its nature and character

to the point where it can no longer be considered a book?

Is this combination of “artistic” and “domestic artefacts”, and their ongoing temporal

and narrative reconfiguration, related to the typology of the book (in whatever form

we understand it)?

Or do these hybrid artefacts become other “things,” autonomous from a notion

of the book?

Is all of this activity informed/supported in its modus operandi by the making of books?

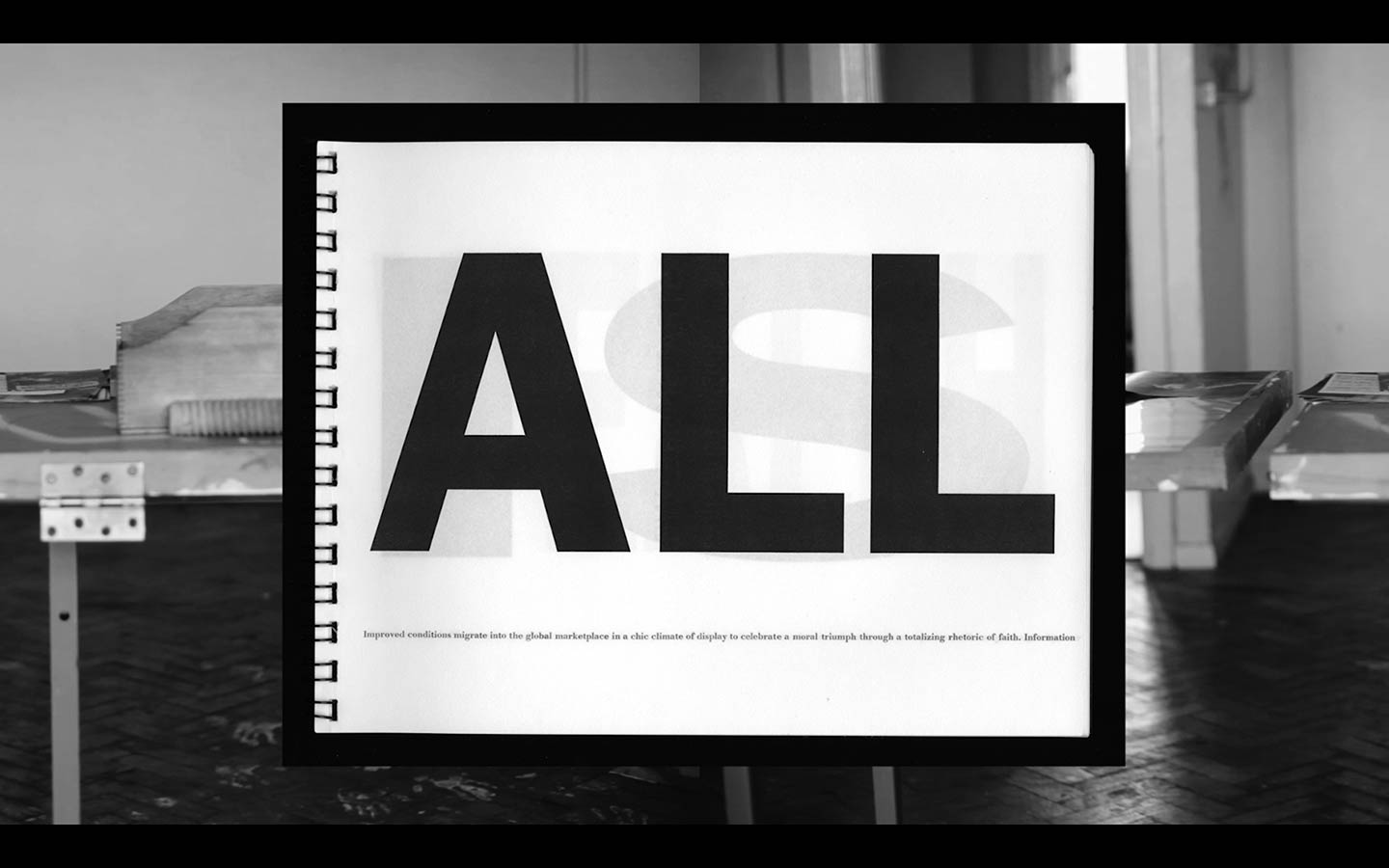

Is the totality of this live/work space a book, i.e., a great “sandwich of materials,”

as Dieter Roth defined the artist’s book?

Is the “immersive” practice itself articulated with the methodologies of creation,

reading and transgression of the “expanded” book?

This reflection is based on two works of different nature and production process,

related to the period in which I experienced them and conversations I had with paula

during my visit to her space, in Woolwich, South–East London.

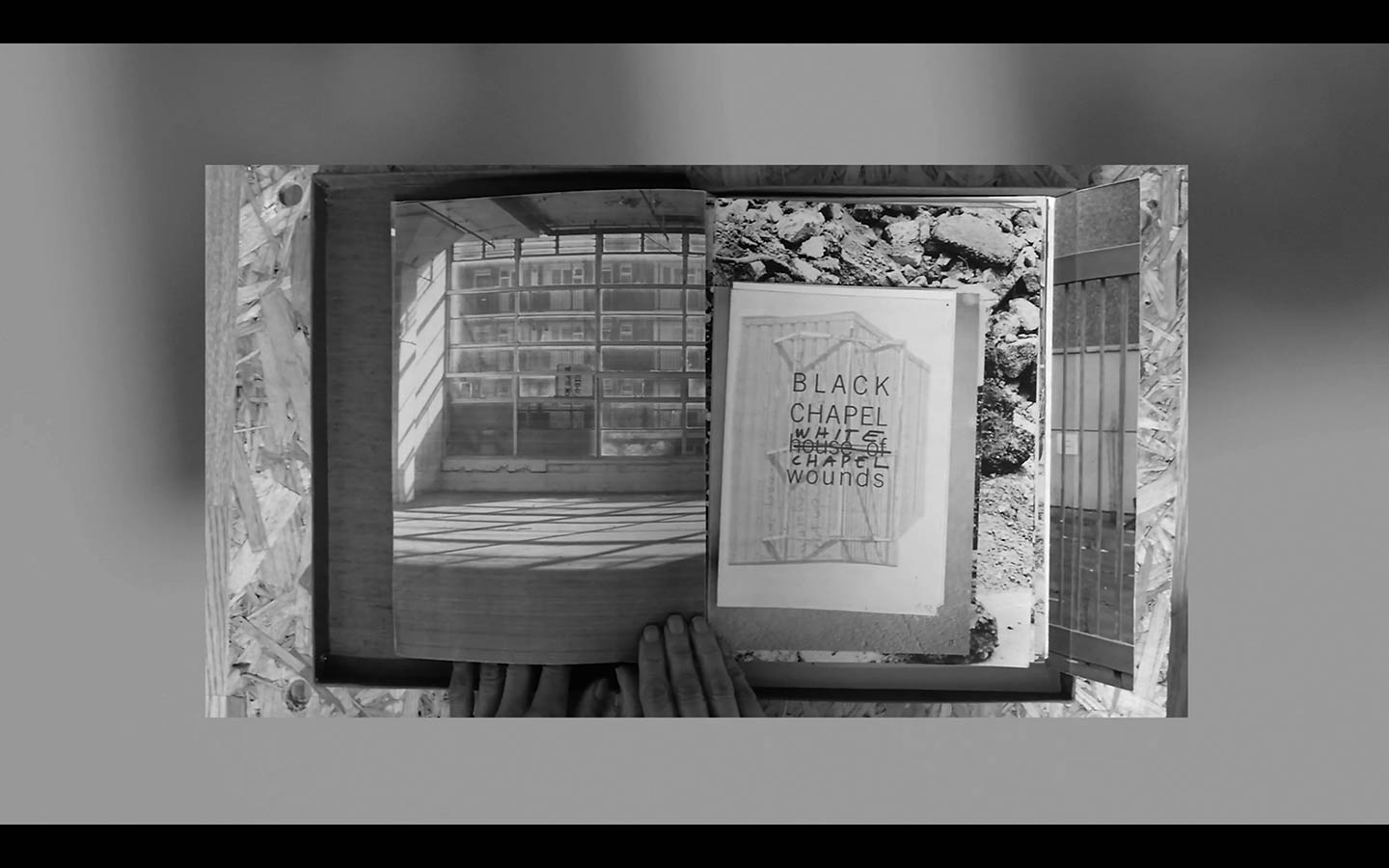

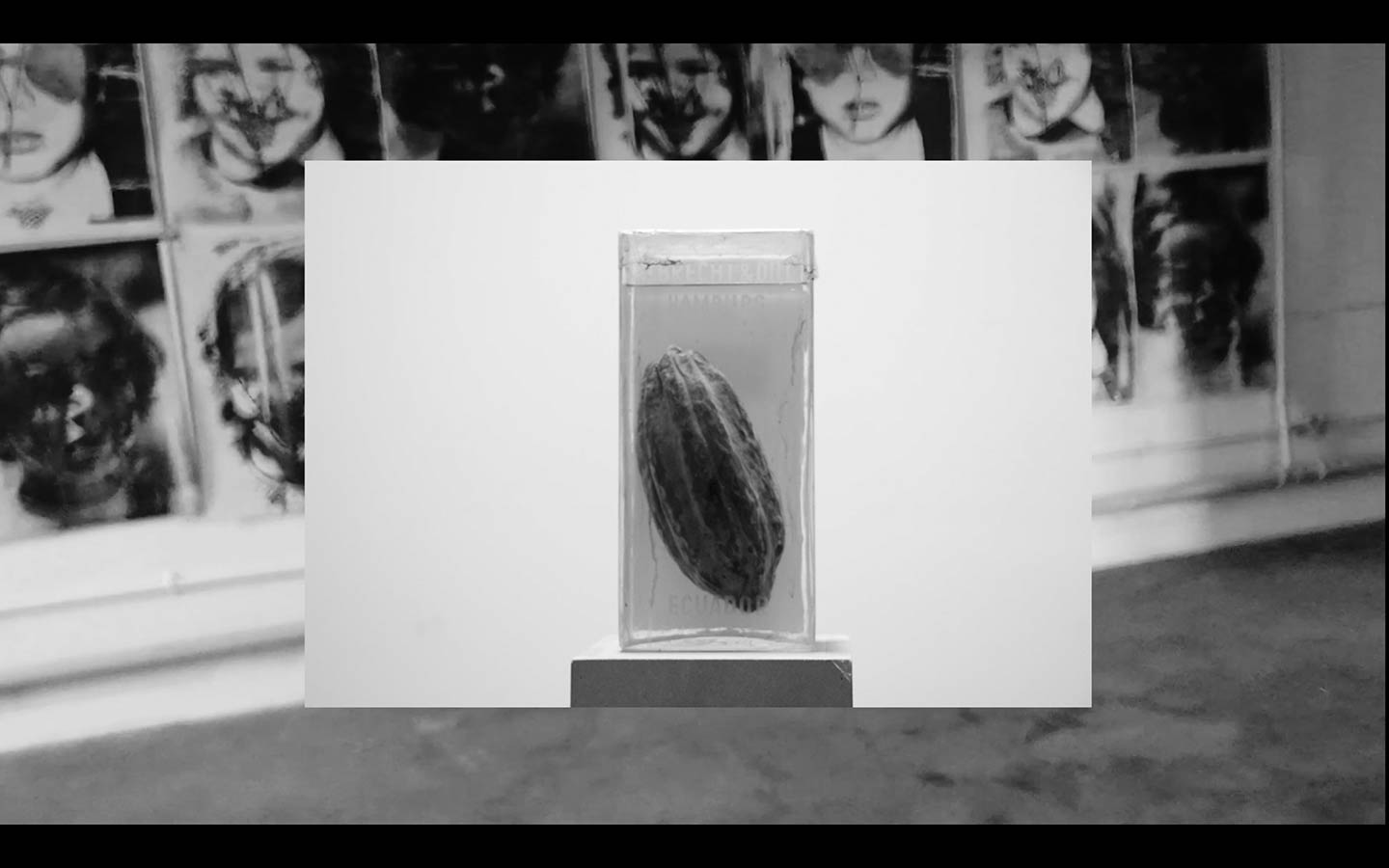

These works are Blackchapel and Untitled (working title), two “sandwiches of materials” installed throughout the building. I investigate whether it is possible to apply the notion

of “expanded field” to these works, and relate this to the condition of “contemporaneity.” Finally, I discuss whether collections and books share the same condition.

Autoethnography

The field of creation and publication of artists’ books has a past that begins with the artistic vanguards in the early 20th century and had its resurgence and theoretical reformulation from the 1960s onwards. In recent years, the artist ‘s book has been, for some, the chosen vehicle for expression and exhibition of their work, becoming itself an alternative to the institutional art gallery. Furthermore, it is almost impossible to assign definite boundaries and characteristics to what is considered an artist’s book; it is rather in the questioning of its limits that emerges an expanded practice that is at the edge (or beyond) its definition as book.

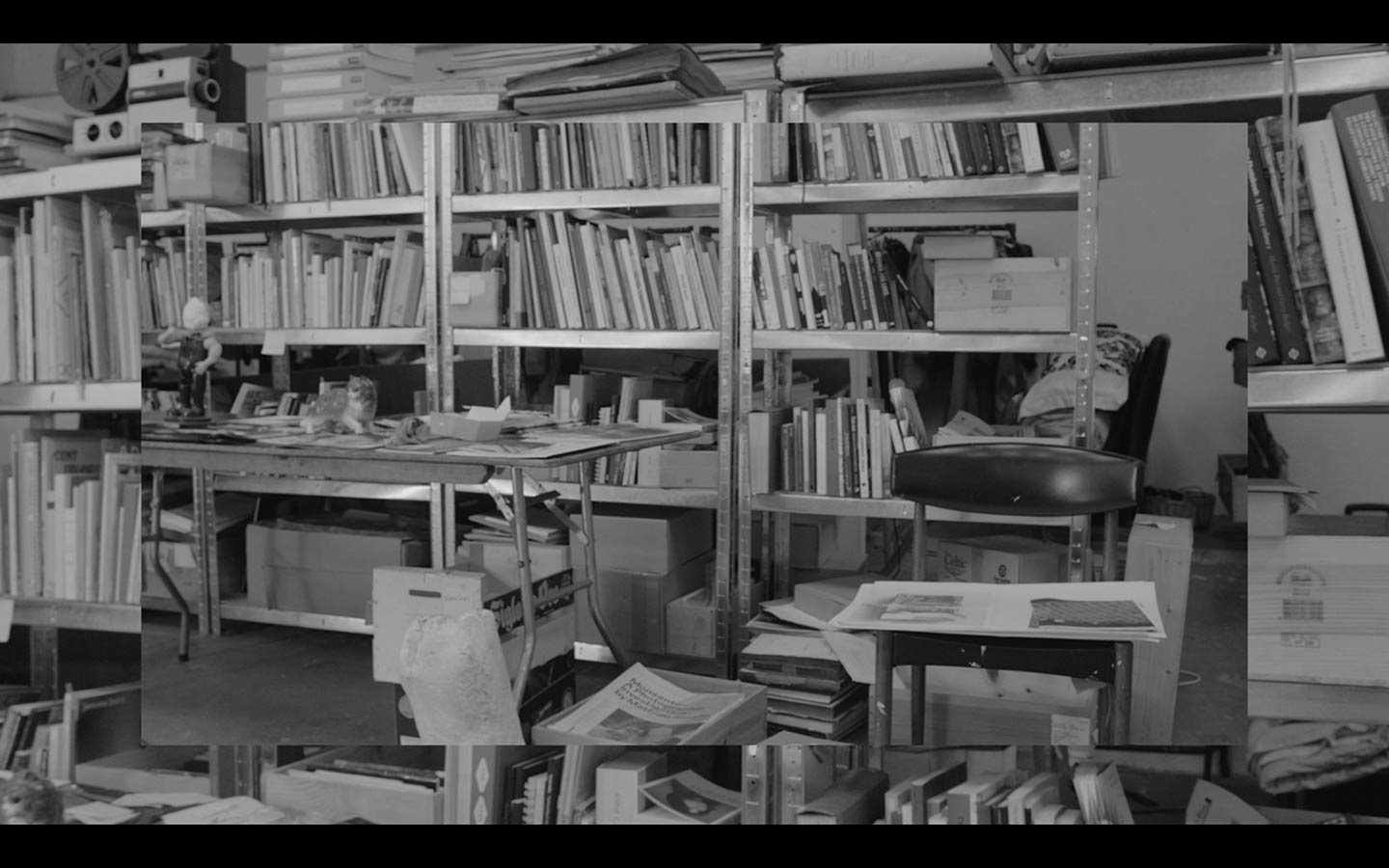

Instead of an activity exclusively focused on the making of artist’s books, paula’s main concern is the immersion in the places where she lives and sources her materials from. These materials are investigated in their context, history, provenance and relationship to the community. As well in relation to the tripartite use she makes of the space, where living space is indistinguishable from studio and exhibition spaces.

This practice and its ethnographic research methodology assume the characteristics of an autoethnography, similar to that outlined by Tony E. Adams, Carolyn Ellis and Stacy Holmes Jones:

Autoethnography is a research method that uses personal experience (“auto”) to describe and interpret (“graphy”) cultural texts, experiences, beliefs, and practices (“ethno”). Autoethnographers believe that personal experience is infused with political/cultural norms and expectations, and they engage in rigorous self reflection—typically referred to as “reflexivity”—in order to identify and interrogate the intersections between the self and social life.

Although the methods of this immersion process vary according to the location of paula’s house–studio–gallery, there is always a simultaneous redefinition of her identity. The artefacts created as a result of this process—installations and objects—are transient and exist in a state of permanent mutability. Books are created before, during and after the making of these installations, sometimes with the materials used in them and sometimes also integrated into them.

About paula roush

To begin with, we shall use paula’s own comments on her approach to clarify her live / work process:

The visual interpretation of space production, from everyday spatial practice to contested spatiality, has been a consistent pursuit of my practice. Over the last five years, the focus has been the artist’s house–studio–gallery, a space defined by its triple purpose of living, creating and curating. Since 2015, I have occupied four different live–work self-contained units, all interim spaces located in South–East areas of London. I transformed them into temporary house–studio–galleries and my photographic practice became an enquiry focused on its intimate spaces and outdoors context, an expanded container for domestic life, artistic production and exhibition–making.

These interim spaces, being first and foremost archaeological sites of the contemporary past, provide opportunities to explore a variety of methodologies for photographic practice, including psychogeography and autoethnography. How to represent the psychic experience of architecture and urban space? Trace the buildings’ past histories, personal and social narratives contained within their walls, memories of industrial labour, materials and services? Document my presence and involvement in the transition into cultural economies?

My research project into photobook publishing has developed in parallel, each bookwork mirroring this probing into the psychic nature of architecture and the poetics of lived space, both interiors and urbanscape. The reading experience is, in each case, an interplay between the architecture of the building and the visual structure of the book.

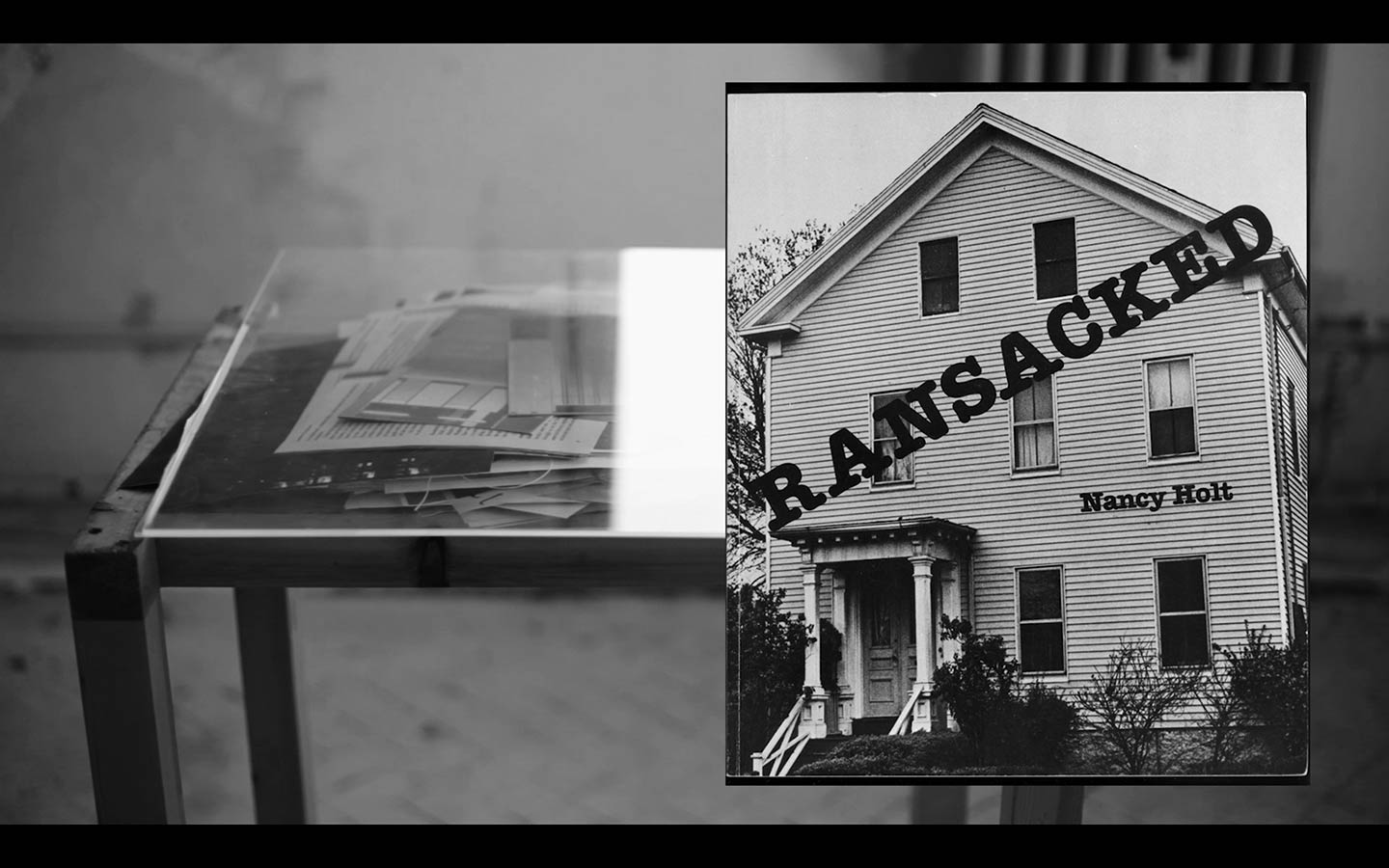

paula introduces herself as photographer and founder of msdm, a house–studio–gallery for photographic practice. In her works she interweaves her own photography with orphan photographs, found objects and media–archival research to draw links between experiences of contemplative photography and synchronicity in everyday life. The presentation formats include: installation, art publishing, performative installation and curatorial projects. She is a lecturer in art photography and photobook publishing in the School of Arts and Creative Industries at the London South Bank University. Her photobooks include Nothing to Undo, Bus-Spotting+A Story, Super-Private and Queer Paper Gardens. They are in public collections, including Victoria & Albert Museum’s National Art Library, London and Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET), New York. They’ve also been recognised by Kassel and Arles photobook awards and Sheffield International Artists’ Books Award.

To be a property caretaker

It is fundamental for the realisation of paula’s life and work, the possibility of occupying large buildings. These are interim spaces available for a limited period of time, and for a hybrid use that combines live–work spaces with exhibition spaces. Their spatial typologies are interchangeable and due to their scale, even after adding furniture and artwork, they appear empty. This results in the spatial juxtaposition—in a state of permanent mutability—of artefacts related to a triple interconnected experience of: location, recombinant structure of new juxtapositions, lending into itself into new “final” objects. This process reflects the permanent reformulation of her personal identity that takes place through the constant and inseparable flow of life and work.

This modus operandi is only possible due to paula’s condition of property caretaker, that is, her ability to occupy real estate properties that are in a transitional period when they are no longer in use and awaiting their reintegration into the real estate market or possible architectural intervention.

The expanded field of contemporaneity

In order to define what we mean by an expanded practice and, by analogy, what can be an expanded book, I use the reflection that Delfim Sardo articulates around Rosalind Krauss’s concept of sculpture in the expanded field:

...sculpture in the 20th century consists of a permanent reworking of the absence, of a body that is no longer there—because it is elsewhere, because it has been metamorphosed, because there is only a hint left of it. In that process, sculpture is expanded; it is expanded so much that it ceases to be itself to become the most difficult artistic genre to define, the most difficult to circumscribe...

We can extrapolate this condition of the metamorphosed object to the artist’s book, only a hint left behind, replacing a body no longer there.

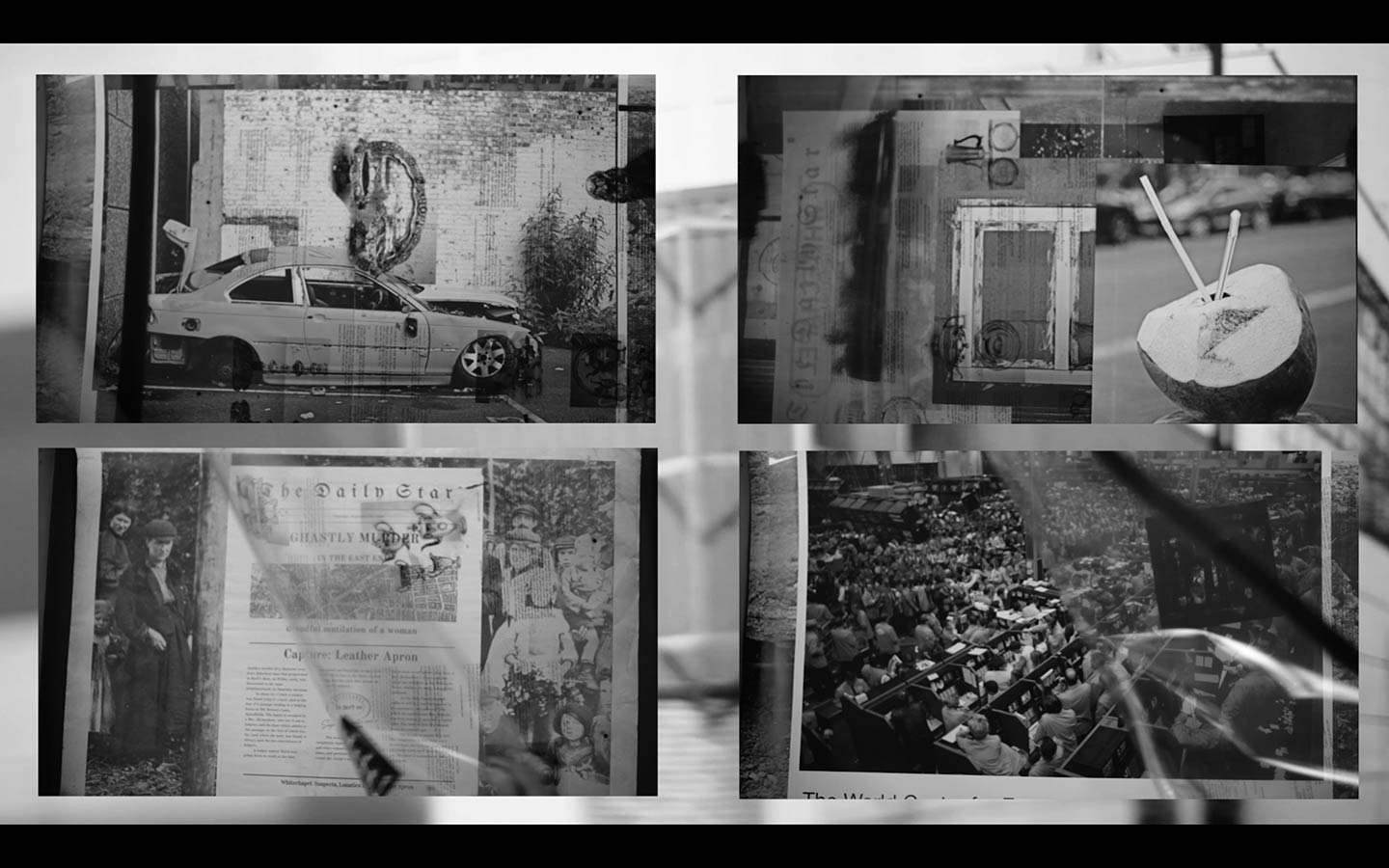

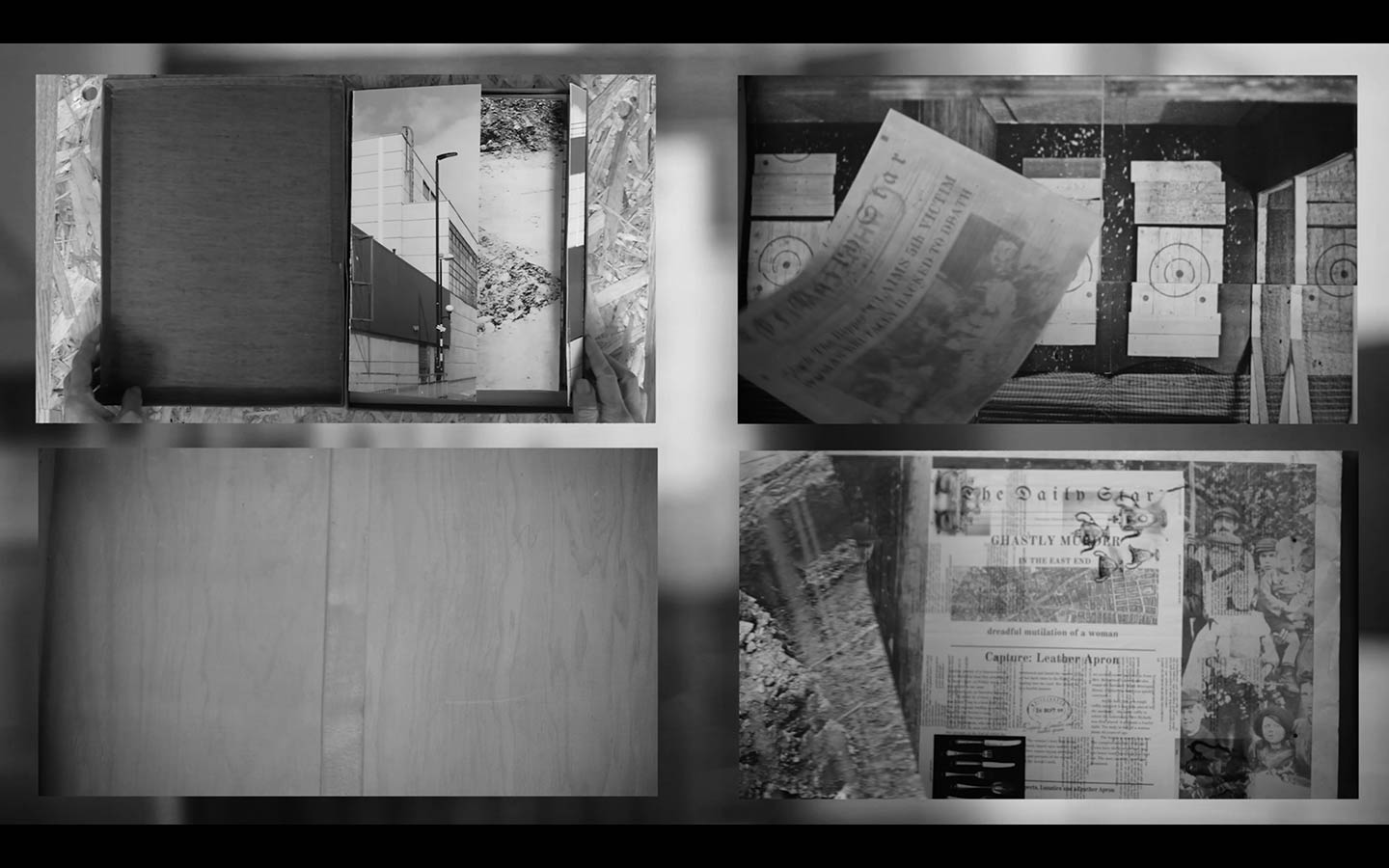

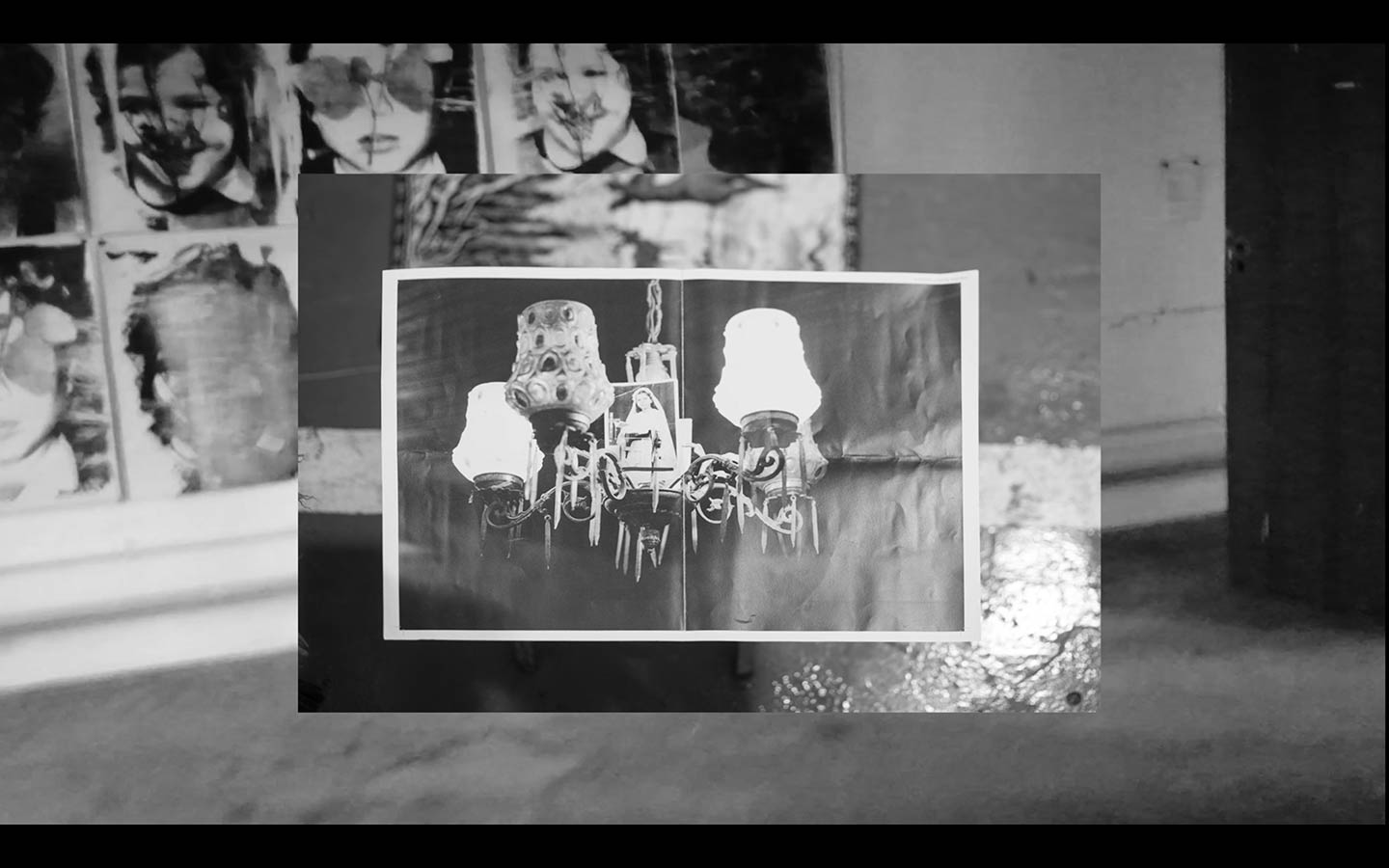

Let’s take the example of Blackchapel project. It is a book that incorporates and works through paula’s personal feelings in relation to the space she occupied in Whitechapel from 2015 to 2017. It is a psychogeographic investigation of East London, with literary references to the occult mythology of Whitechapel including photographic evidence related to Jack the Ripper’s Whitechapel crimes. And it is as well, in my opinion, a projection of her own anxieties regarding the immense deserted space of the building she occupied. Psychogeographic research is complemented with further documentation connected with the planning application for the site and related panoramic vistas of London, sourced from arquitectural codes of practice. This bookwork is not officially published yet and is still undergoing a reformulation, where different narrative voices are tried out. There is an edition narrated from a personal point of view, in which paula puts herself in the role of the photographer, tracing her experience, including moving into the building and discovering the occult sources; and there is another edition told from an investigative perspective, unfolding in a third person, where her role is that of an editor that organises and sequences the material “reaching her hands.”

All the materials mobilised in this project—her own photographs, artefacts sourced from the building site, literary research and archival material—were used in the exhibition “Evidencing The East End,” first installed in the Stepney Way warehouse, Whitechapel, in 2016, inaugurating the spatial model of the house–studio–gallery. This material has been reconfigured in the current space in Woolwich, being distributed in several “clusters” or “constellations,” together with other elements of different provenance, some in the state of “sandwiches.”

I can see in this constant reworking and multiple reconfiguring of materials the metamorphosis that Delfim Sardo identifies in the field of expanded sculpture, made visible in the ongoing corporeal mutation of the book, becoming thus an expanded practice of the book.

I can also find in this work process, the mutability that allows it to exist beyond a specific time frame. The contamination that results from the aggregation of materials from different sources and contexts (which constitute the “sandwiches of materials”, the installations, the agglomerations and the books) fits in the contemporary condition that Nuno Crespo describes as follows:

Creative and exhibition practices are characterised, according to Bishop, by the effort to trace the physiognomy of the present. This physiognomy is temporal and is characterized by an anachronistic dynamic, that is, the artistic present is a place of contamination that develops in a non–chronological horizon containing the possibility of making multiple crossings, syntheses, collages and junctions. That is why Didi–Huberman, when trying to think art history, proposes an atemporal methodology and, following Warburg, pathological, looking for logics of influences and contaminations and not affiliations or chronologies.

We can also infer that the live–work method used by paula (which I call “immersive”) is similar to the process she uses to make books and the subsequent objects that derive from them, whether constellations of materials or sandwiches. This is Crespo’s “anachronistic condition” where “the artistic present is a place of contamination,” and the visual structure of the work organised according to a logic that is not chronological, but follows other logics. This “immersion” process, and the processes of book construction–deconstruction share the same method. In other words, life and work are “constructed” in a similar way.

Collections and books

The issue of the similarity between collections and books is a fundamental one to clarify whether the totality of paula’s practice is guided by the making of a book. We can infer this from an extract of paula’s writing (in this essay) where she states that, “The reading experience is, in each case, an interplay between the architecture of the building and the visual structure of the book.” What we need to know is whether, as paula tells us, the experience of “reading” the entire house–studio–gallery and the different “constellations” of materials installed inside it, is similar to the reading of a book and, therefore, the occupation of the building has a visual structure similar to that of a book. To clarify this hypothesis, we use the essay “Books as Collections: Dieter Roth’s Artists’ Books as Case in Point” by Barbara Bader, identifying the “constellations” of materials existing in the building, either as collections or as books, be they books in the strict sense, be they “sandwiches” or mere agglomerations of materials.

Barbara Bader tells us in her essay that books and collections share more than an affinity in their constitution. A collection is understood as a unit of objects agglomerated systematically and kept in a particular space, whether a box, an office, a room or even an entire building (note taken). She adds that a book consists of a number of pages aggregated within a cover, which together form a conceptual unit.

It appears that there is not a total identification between collection and book. However, as Bader points out, by cognitively isolating or objectifying information from the outside world, both books and collections have the ability to contextualize their content. On the notion of “another space” or “heterotopia,” Bader quoting Foucault, describes them as “places…outside of all places,” and concurs with Kate Linker that artists’ books provide “an alternative space.”

We can find in paula’s “sandwiches of materials,” that most elements come from a photographic matrix, albeit with different materialities and typologies, including typographic stencils, photographic posters or prints of images from publications and even paula’s own photographs printed in large format. Those works share the condition referred by Barbara Bader, of being “another space” that objectifies information and that contains, in all its elements, a common characteristic: its photographic provenance.

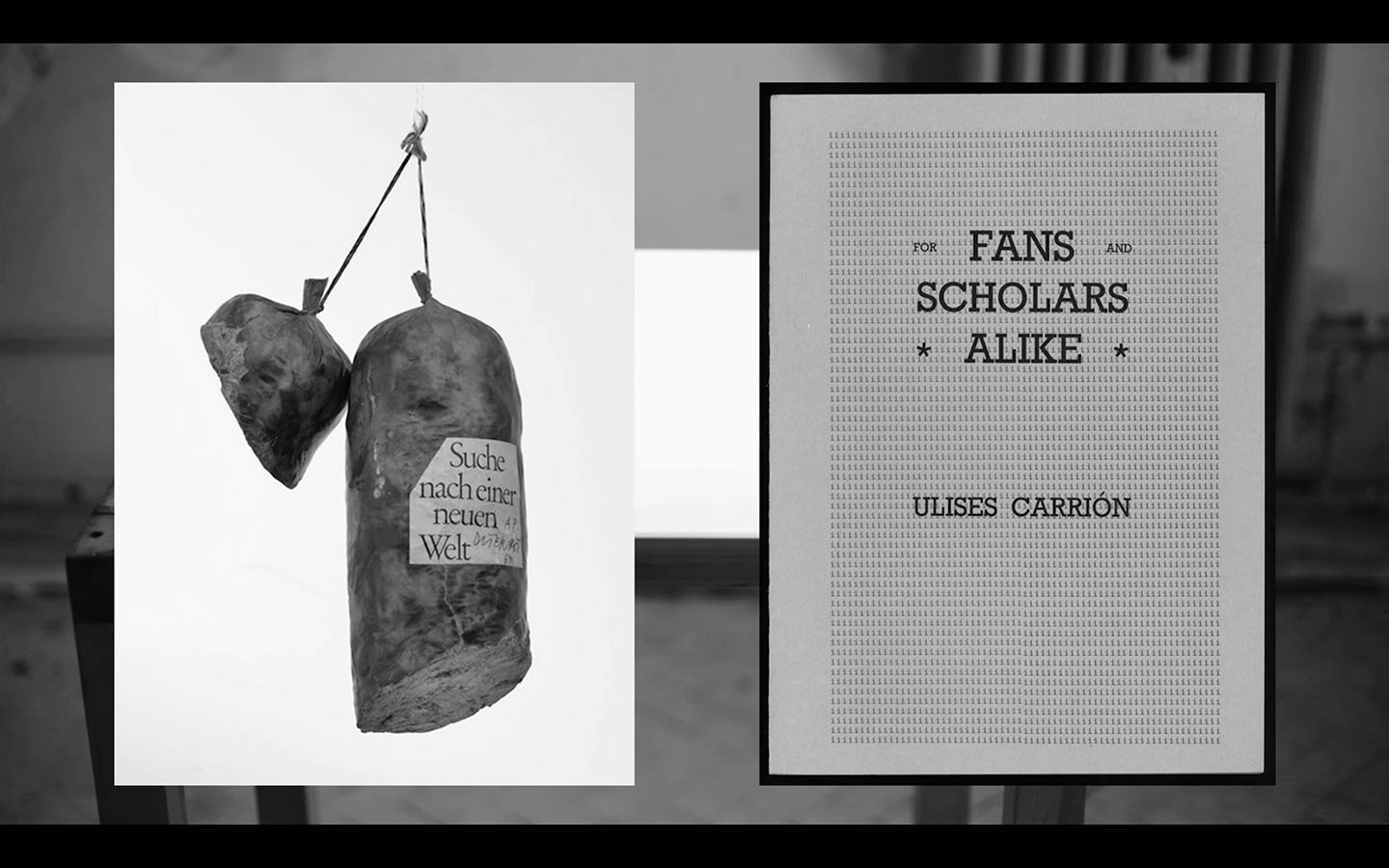

But the definitive combination of these two “states”—collections and books— that includes materials as works in progress and materials as works of art being exhibited, is clarified with Bader’s invocation of Ulises Carrión’s 1978 essay The New Art of Making Books, where the commonality between books and collections is attributed to their temporal or spatiotemporal dimension. By defining the pages of a book as “a sequence of spaces,” he calls attention to the fact that the act of reading and of turning the pages demands time and, consequently, that the book must be perceived as a “space–time sequence.” As we know from experience, moving through time and space —literally or metaphorically—is fundamental to any collection, be it in a gallery or museum, or the more intimate context of a collection of stamps or coins. Both the curator and the book designer have a wide range of strategies to slow down or speed up the narrative, and consequently to influence the beholder’s movements and spatiotemporal experiences.

In other words, the “sandwiches of materials,” be they installations, agglomerations or books, when inserted in the space of the house–studio–gallery, they all share this condition of being part of a space–time sequence and share with the building a narrative structure. And this, we conclude, provides an experience similar to the reading of a book.

THE ART OF IMMERSION: COLLECTION, RESEARCH, DISPLAY

Considering the experience of “reading” the whole house–studio–gallery (and the “constellations” of materials installed within) is similar to reading a book, what we aim to investigate in this chapter is whether the occupation of the building–and the totality of paula’s method that we call “immersive”–has a visual structure similar to a book.

In this regard, it is adequate to ask the following questions:

Can paula’s entire life and work process be incorporated into one single method?

Is all her activity and artistic production guided by the same principles?

Can we find the principles that guide her practice?

Could her method of living and working be analysed within the theoretical framework developed by Rancière?

Can we, within this analysis, identify the paradigmatic processes behind its functioning?

Immersion

As we’ve seen before, paula’s main concern is her immersion in the places where she lives and sources materials from. These materials are investigated in their context, history, provenance and relationship to the community. As well in relationship to the tripartite use she makes of the site, where living space is indistinguishable from studio and exhibition spaces.

This practice assumes the characteristics of an autoethnography, and although the methods of this immersion process vary according to the location, there is always a simultaneous redefinition of her identity. The artefacts created as a result of this process— installations and objects—are transient, existing in a state of permanent mutability.

Mutability is transparent in paula’s spaces because there is no distinction between private and public space, since there is no clear separation between spaces dedicated to daily life and exhibition spaces. Likewise, there is no separation between studio space and exhibition space (as we have already mentioned), therefore it is not clearly distinguishable which materials are in a state of “raw materials” or in a state of “completed works.”

Add to this the constant recombination of the exhibited artefacts, whose materials are permanently moved between “collections” (agglomerations of materials or “sandwiches of materials” and personal files) and books, and vice versa.

The analysis of paula’s live / work context that I presented previously as “immersion,” as well as her guiding principles will now be queried at the light of the theoretical framework assembled by Jacques Rancière in two of his books The Future of the Image and The Emancipated Spectator, as well as the “Glossary of Technical Terms” written by Gabriel Rockhill, published as an appendix to The Politics of Aesthetics- The Distribution of the Sensible.

I will use the work titled Blackchapel as my case study to illustrate the process of immersion I previously analysed in a more general way. Using the concept of “immersion” and this particular example as starting points, I will highlight three key operations of this method—collection, research and display of materials—and investigate whether the notion of “dispositif” advanced by Rancière is suitable to describe these operations and paula’s artistic processes.

Dispositifs

I propose to analyze here whether paula’s method of immersion and its key operations—identified as i) collection ii) research, and iii) display of materials— may be equated with “dispositifs,” in the sense that Rancière gives them. That is, are these operating processes the same as “dispositifs”?

Perhaps we can equate those three operations—collection, research and display of materials—to the articulation that Rancière, in the words of Rockhill, makes between three things: ways of doing, their respective forms of visibility, and ways of conceptualising both. Following this approach, we will try to equate the three operations of “immersion” to what Rancière calls “a regime of art.”

A medium is not a ‘proper’ means or material. It is a surface of conversion: a surface of equivalence between the different arts’ ways of making; a conceptual space of articulation between these ways of making and forms of visibility and intelligibility determining the way in which they can be viewed and conceived.

It is noted that Rancière attributes an operational sense to “ways of doing” when delimiting the medium’s field of attraction, he refers to it as a surface of conversion or equivalence between the ways of doing (which we can designate as operations) and the different arts. Rancière articulates these with the forms of visibility (which I identify with “display”), this articulation being determinant to the way different arts can be seen and thought (which I identify with “research”).

We identify, thus, the three key operations of the immersive process with the operations that Rancière lists in his definition of medium. But are these operations identifiable with “dispositifs”? Let us quote Rancière again:

The point is not to counter-pose reality to its appearances. It is to construct different realities, different forms of common sense— that is to say, different spatiotemporal systems, different communities of words and things, form and meanings.

A dispositif is, after all, a “community” of linguistic elements that are objectual, formal and induce ways to perceive, to be affected by and attribute meaning. It seems to me that “dispositifs” are mechanisms that through operations (ways of doing) conceptualise and make visible “new communities” or new spaces “of words and things, shapes and meanings.” In other words, they create new circumstances for the elements and their meanings, which are, after all, what the key operations (“collection,” “research” and “display”) of paula’s operating method (“immersion”) do.

Dispositif I: Collection

Upon her arrival in Whitechapel, paula notes that “I started to realise that there were structural elements of the Whitechapel experience, which were elements of alienation in relation to space.” paula’s perception of the space to which she moved (both the building and its context) provided her, as we have already seen, with an opportunity to work through “her own emotions related to the space,” which began with the collection of materials from her surrounding environment (of the most varied typology). These were installed on site, operating a rearrangement of her immediate context of life and artistic work, with new materials and in an interdependent form (as previously mentioned), a rearrangement of her personal identity data, developing a process similar to that expressed by Rancière:

The labour of art thus involves playing on the ambiguity of resemblances and the instability of dissemblances, bringing about a local reorganisation, a singular rearrangement of circulating images. In a sense the construction of such devices assigns art the task that once felI to the “critique of images.”

For paula, these operations are, however, less “modest,” more “radical” and “demystifying” than Rancière indicates as being characteristic of artists who do a “critique of images,” since according to him artists tend “to dedicate their operations to more modest tasks.” In fact, for paula there is a recombination of materials according to affinities (dynamic or changeable) that she finds (in a permanent work in progress), endowing the new agglomerations (sandwiches, clusters or constellations) with a more radical symbolic charge, I would say, than that Rancière attributes to artists’ actions.

Dispositif II: Research

The work of research and (re)signification of materials mobilised in Blackchapel– photographs and artefacts constructed from contextual survey and archival research– constitute, as we have already seen, a process of “contamination” that has an “anachronistic dynamic.” Thus, the structuring logic of this dispositif (the investigation) is not, as we have already seen, necessarily chronological, but of a different order, as is the case for example with the combination, in Blackchapel, of the psychogeographic survey of the area with the planning application for the site, a reality that paula translates by saying: “I thought of articulating a discourse on the occult of Whitechapel, of which there is an extensive bibliography, with the psychogeography of East London and a photographic investigation of everyday urban space.”

As we can see, there is no intention here of the literal and chronological transcription of a report, but rather, it is a work on the fissure of the representational “disposif” that Rancière points out:

Thus, the problem does not concern the moral or political validity of the message transmitted by the representational dispositif. It does concern the dispositif itself. Its fissure shows that the effectiveness of art is not to transmit messages, provide models or decipher representations.

That is, it is about finding other structuring logics that result from the rearrangement of the materials mobilised, researched and constructed. A process that Rancière formulates as follows:

It consists first of all of the dispositions of the bodies, it consists of the cut-out of spaces and singular times that define ways of being together or separately, facing or in the middle of, inside or outside, in proximity or at a distance.

And this is because in the action of this dispositif there is no linearity between cause and effect. As Rancière explains, there is no sensible continuity between, on the one hand, the production of images, gestures or words, and, on the other, the perception of a situation that compromises the spectators’ thoughts, feelings and actions.”

Dispositif III: display

The “display” - or what appears to us as “complete works” - is not, as I have already pointed out, a final state. See what paula says about Blackchapel’s “display”: “It is on several tables because now I’m trying to resolve it as an installation.” Its condition is recombinat, always transitory, and can, in a circular process, return to the condition of “raw materials.” Because, as already explained, collections (“sandwiches,” installations and agglomerations) and books— what constitutes the “display”—share with the building this condition of being a space–time sequence, and a narrative structure. The movement of transformation of the “display” is inherent to the construction of narratives: of objects, space and the entire process of immersion.

We can identify in this narrative “disposif” of “display” an “aesthetic efficacy” that, being grounded in its unpredictable mutability, challenges any fixed relationship between creative production and a “determined effect on a specific audience.” Since, as this is the case, “a critical art is an art that knows that its political effect happens through an aesthetic distance.”

MUSEOGRAPHY OF THE ARTIST’S STUDIO: THE ARTIST’S MUSEUM

This chapter analyses whether the term “museography” is applicable to paula’s practice, and what are the precise contours of this “museography” in the activity that paula exercises in her live, work and exhibiting spaces, which she calls house–studio–galleries.

This investigation into the musealisation of paula’s studio started in the two previous chapters with the notions of spatio–temporal sequencing in the space of the building, and paula’s live–work method, a triple “dispositif” which I designated as “immersion.” It is furthered in this chapter in relation to the concept of museography and Kettle’s Yard House–Museum, a museum model I investigate in reference to paula’s house–studio–gallery; and, finally, with the applicability of the notion of Artist’s Museum to her space.

Museography

I am interested in understanding the extent to which paula’s spatial activity comprises a “museographic program” and whether paula, like a muséographe, executes it as André Desvallées and François Mairesse define it:

More generally, what we call the “museographic program” encompasses the definition of the contents of the exhibition and its imperatives, as well as the set of functional relationships between the exhibition spaces and the other spaces of the museum. This definition does not imply that museography is limited to the visible aspects of the museum. The muséographe, as a museum professional, takes into account the requirements of the scientific and management program of the collections, and seeks an adequate presentation of the objects selected by the conservator. S/he knows the methods of conservation or inventory of the museum objects. S/he elaborates a scenography based on the contents, proposes a discursive construction that includes complementary mediations that can help understanding, in addition to being concerned with the demands of audiences, mobilizing communication techniques adapted to the good reception of messages.

This possibility of artists being able to constitute their studios into museographic spaces is of particular relevance for its potentials benefits. Artists may dispense with the institutional art circuit, escaping all associated premises and conditions: need for validation, subjection to the mercantilist logic of the art market, exposure to institutional criticism, acceptance of “suggestions” from gallery owners and curators and, finally, loss of control over the conditions of production and exhibition of their work. Short–circuiting all these conditions, by museographing their studios, artists are thus giving their work the institutional (museal) status, transforming their production into musealia, that is, in a “museum object” that integrates the museological field.

The artists’ total control over the way their work is exhibited, communicated and preserved—three activities that are part of the museographic process—offers original formats and not standardized approaches, perfectly adjusted to artists’ life style, work and identity.

Devallées and Mairesse write: “According to common sense, museography designates the becoming of a museum or, more generally, the transformation of a life centre, which can be a centre of human activity or a natural site, into some kind of museum.”

This is the first issue we face in applying the term “museography” to paula’s exhibition practice, since her spaces are not museums nor are they expected to be. It is also a question of whether paula’s live–work–exhibition process fulfils all the characteristics of the museographic process, as stated by Teresa Azevedo:

As a scientific process, museography “necessarily comprises the set of museum activities: a work of preservation (selection, acquisition, management, conservation), research (and therefore cataloguing) and communication (through exhibition, publications, etc.).

Can we identify in paula’s activity the work of preservation, research and communication inherent to the museographic activity and, if so, in what way do these specific forms function in paula’s artistic practice?

Let us highlight the consequences that the museographic process creates in relation to the objects subject to it. Let’s consider what Teresa Azevedo writes on this matter:

In fact, any museographic process necessarily implies a change in the status of the museographed object. According to the definition proposed by ICOM as one of the key concepts of museology, museography designates “becoming a museum or, more generally, the transformation of a life centre, which can be a centre of human activity or a natural site, in some type of museum,” characterized by the “extraction, physical and conceptual, of something from its natural or cultural environment of origin ... transforming it ... into a ‘museum object’.” However, museography does not only simply imply “transferring an object to the physical limits of a museum ...”, it also takes place when, through a “change of context and selection process, the “thesaurisation” and presentation operate a change in the status of the object.

Do objects change status within the house–studio–gallery? Is there a change in context? Does the physical and conceptual exclusion of the objects from their origins, transform them into “museum objects”?

The museographic process of artists’ studios, is considered by some an anomalous process, as suggested by Azevedo:

Although the museography of artists’ studios is one of the most obvious types of integration of the studio into the museum, it is far from being a simple and consensual practice. In fact, it raises many questions about the status, role and effective utility of the studio in the museological context (Vincent, 2011); there are several approaches proposed and / or critiqued in the theoretical reflection on this practice, which in turn contributes to the richness of the discussion on the topic. Barbara Dawson, for example, says that any project of musealisation of artists’ studios tends to reveal the greatest difficulties inherent in their own realisation, which are mainly related to the way in which a private space can be transformed into a public exhibition space: “The studio is a personal artist’s enclave where raw materials, instead of complete works, dominate. How can this be presented?” (Cappock, 2005). Daniel F. Herrmann, in turn, is sceptical about the definitive transposition of an artist’s studio to a museum, even referring that this process is an anomaly.

In fact, paula’s spaces reflect the problematic of transforming a private space into a public space, since in her case there is no clear separation between spaces dedicated to daily life and exhibition spaces, and neither is there a separation between studio space and exhibition space, so it is not clear which materials are “raw materials” or form “complete works.” Add to this the constant recombination of exhibited artefacts, whose materials are constantly moved around between “collections” [agglomerations of materials or “sandwiches of materials,” personal archives (classified by place and date)] and books, and vice versa.

Kettle’s Yard

Kettle’s Yard is a house-museum, and in 2018 it was the object of an architectural intervention that, whilst preserving the house in the exact conditions in which Jim, its co-creator, left it, endowed it with new spaces, including a floor dedicated to educational programs, an improved gallery (of the “white cube” typology, built in 1970), a cafeteria and a new entrance to the museum.

The museum has a regular program of contemporary art exhibitions, musical performances, workshops and a program of talks by artists and curators about art, media and archives. Its website includes documentation of these conversations, related exhibitions, as well as the museum’s collection database.

The house-museum was created in 1956 by Jim Ede and his wife Helen Ede as a result of their search for: “a living space where works of art could be enjoyed …, where young people could be at home unhampered by the greater austerity of the museum or public art gallery.” Also, according to the museum’s page, in 1966 Jim Ede donated the house and its contents to the University of Cambridge.

Jim Ede and Helen Ede lived in Kettle’s Yard between 1958 and 1973. Jim was a curator at the Tate Gallery in London in the 1920s and 1930s. It was thanks to his friendships in the art world that he brought together an admirable collection of modern British art, as well as foreign artists, including Joan Miró and Constantin Brancusi. In the house, Jim carefully positioned these works of art alongside furniture, crystals, ceramics and natural elements, trying to create a harmonious whole. His vision of what would become a museological space did not include

An art gallery or museum, nor … simply a collection of works of art reflecting my taste or the taste of a given period. It is, rather, a continuing way of life from these last fifty years, in which stray objects, stones, glass, pictures, sculpture, in light and in space, have been used to make manifest the underlying stability.”

That is, Kettle’s Yard in its origin was—and still is, since this didn’t change—an exhibition space in a domestic environment open to the public and without ever ceasing to be a live–work space for Jim and Helen, which is identical to what happens in paula’s house–studio–gallery. However, the existence of the studio in paula’s space, creates an important distinction in relation to Jim and Helen’s house–museum space and their studio–museum, a distinction that we can perhaps characterise as Azevedo does:

House–museums are distinct from studio–museums in that in the latter it is the work space itself that justifies and is at the origin of the musealisation process, and it is this space that guides all the definition, activities and programming of the space.

Let’s examine if paula’s house–studio–gallery also fits ICOM current definition of a museum, mentioned by Devallées and Mairesse:

The professional definition of a museum best known today remains the one found in the statutes of the International Council of Museums (ICOM), 2007: “The museum is a permanent, non-profit institution, serving society and its development, open to the public, which acquires, preserves, studies, exhibits and transmits the material and immaterial heritage of humanity and its environment, for the purposes of study, education and delight.”

The attributes of this definition are fully met by Kettle’s Yard in its current version. However, paula’s house–studio–gallery has particularities that differentiate it from the concepts and methods normalised in the activities of some of the institutionalised museums, namely:

It is not an institution;

It carries out activities that are not always for profit, such as exhibitions and collaborative research, without disregard however, for the commercial value and sale of its artistic production (installations and publications);

It is not, exactly, at the service of society because it aims at a very segmented public (as it happened with Kettle’s Yard in the beginning);

If it transmits the material and immaterial heritage of its environment, it only does so within the scope of its projects and within the scope of the immersive process (paula’s live–work method) that we have already described. The same applies to its objects of “study, education and delight.”

In other words, they are all activities of a personal nature, which are not intended to address the general public, without distinction, which is the primary condition of a museum.

The artist’s museum

The musealisation of paula’s house–studio–gallery can be contextualised by the critique of the contemporary art museum and its functions that emerged in the 1960s. Let’s see what Elisa de Noronha Nascimento says about this:

In the meanwhile, what is perceived as a distinct reaction, typical of this second phase of the contemporary art museum, are the strategies that many artists have found/find to problematise the museological structures and discourses. Two of these strategies we choose to highlight are: the appropriation of the museological language—the collection, the catalogue, the inventory, the exhibition—and the unveiling of its discursive structures as artistic poetics.

In this consideration of what are the main functions of the museum—collecting, cataloguing, investigating and exhibiting—we can find a theoretical and practical framework for paula’s idiosyncratic and specific activities, translated in exhibitions (which she curates in her space with her own works and those by other artists), in the collections (gleaning of materials from the surrounding vicinity and their organization in material constellations) and, finally, in the inventory and cataloguing of the projects that paula elaborates and makes available on her website. The same is true with her catalogues, with the elaboration and printing of her publications and with the formation of her ad hoc archives.

paula’s house–studio–gallery fits neatly within another type of museum spaces, such as the artist’s museum. Let us refer, again, to Nascimento’s writing :

In this context, two exhibitions stand out: the 5th Kassel Documenta, held in 1972 and curated by Harald Szeemann (1933-2005), where for the first time Szeemann will use the term artist’s museum, referring to the relationship between artistic creation and the principle of museum administration, presenting museum models and fictions such as the Mouse Museum (1965-1977) by Claes Oldenburg (b.1929), the Bôite-en-valise (1935-1941) by Marcel Duchamp, and the Museum of Modern Art, Department of Eagles (1968-1971) by Marcel Broodthaers (1924-1976).

We witness, therefore, in paula’s case, another type of space that presents itself as a museum space, alternative to the modern institutional museum.

On that topic, write Devallées and Mairesse:

The museal establishment is a concrete form of museal institution. We can see that the institution’s contestation, or its pure and simple denial (as in the case of the imaginary museum of Malraux [1947] or the fictional museum of the artist Marcel Broodthaers), does not result in a break with the museal field, insofar as this can be conceived outside the institutional framework (in its strictest sense, the expression “virtual museum”, or potential museum - which exists in essence, but not in fact - accounts for these museal experiences at the margins of the institutional reality).

It is undoubtedly in this typology of spaces that we find paula’s house-studio-gallery and it is in this context that we can argue that her live–work–exhibition space is a museal place.

Written by Francisco Varela

This is an abridged version of three separate essays

submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements

for the Degree of Master of Museological

and Curatorial Studies

(Mestrado em Estudos Museológicos e Curadoriais),

Faculdade de Belas Artes da Universidade do Porto

January 2020