ESSAY

Torn, Folded, Curled: Orphan photographs sourced from the Arab Image Foundation

Crafting an archaeology of the recent past, one photobookwork at a time

by paula roush

Presented at

The Archive: Visual Culture in the Middle East

Symposium at the Lebanese American University

School of Architecture & Design

Department of Art & Design

LAU Byblos campus April 5, 2019

Published in

SUPER–PRIVATE: Sourcing from the Arab Image

Foundation Photographic Collections

[ monograph here + ]

End of 2014, right after Found Photo Foundation was featured in Order And Collapse: The Lives Of Archives 1 I was approached by Rima Mokaiesh, then director of the Arab Image Foundation, to know more about the Foundation I had set up in 2008 to rescue orphan photographs. At this point I already looked after several collections that I’d shown in photographic installations,2 and used to create photobookworks.3 However it was not always like this.

The Found Photo Foundation started as a result of a deep trauma due to the loss of several of my own family albums.4 The photographs’ loss was very distressing and I was left with a gap in my photo-biography. The healing method consisted in building an archive of anonymous, dispossessed photographs. Legally, these are known as orphan photographs, as they have lost their genealogy or ownership. There are multiple reasons photos might have become orphan: they may have been lost, stolen, they may have been abandoned following the death of their owners, or they may have simply ceased to be useful and thrown in the garbage, from which they may have been rescued and put back in the market. Whatever their back stories, these orphan photographs provided me with a method to retroactively recapture my past and that of my country.

Has it happened to you that a loss, a breakdown, becomes one of your breakthroughs? Well that happened to me and the Found Photo Foundation has become one of my most successful projects, and ultimately the reason I ended up visiting Beirut in 2015. So when Rima contacted me and we organised a residency at the Arab Image Foundation, I was instructed to choose a collection to work with from the online database. This placed me in a very awkward position. Having my own photographs collections, I can work in a very intuitive manner, the collections are very informal and I can develop work in the studio, working directly from the materials. Looking at the online database I couldn’t get a sense of what to do.

So what if instead of avoiding those feelings, I’d embrace them, and work from a position of ‘not knowing’?5 That’s what I did. What I really wanted was to have some “now time” to explore the library and the collections, because this is a crucial part of my methodologies, to be able to spend time in a site, do site-specific work, and be in conversation with the users of that space, in this case the librarians, archivists and donors. Also, I work at the intersection of different disciplines: photography, publishing, archaeology, conservation, history, bibliography, memory studies and I always need to find a position within an artistic methodology that turns the unconscious into a productive creative force for difference.

In this paper I share how I developed three photobookworks from the Arab Image Foundation photography collections and went on to publish them with Beirut based publisher PlanBey. I share my way of working in a photographic collections environment and collaborating with others to create research-driven photobookworks. I share five anchors of my practice:

- 1. The photographic collection: how to handle a large number of photographs, using the group/series/sequence formula;

- 2. The story-showing technique: a documentary approach to elevate orphan photographs from archival storage to lived experience;

- 3. The photo-text authorial position: how to combine photographs with text and typography for creative disruption of meaning;

- 4. The haptic mode: the sensorial and materiality identity of the book object that engages the reader’s sense of touch;

- 5. The book dummy: the handmade maquette used for project development and get the work seen by partners or a publisher.

1. The photographic collection

When there are hundreds of photographs in a collection, it is very important to see the compound photograph. Similarly, in a photobookwork originated in a collection, there is no individual photograph, all photographs work together to represent the collection’s organisation. It helps to think of three types of organization- group, series and sequence - that can be used to translate the photographic collection into the book medium.6

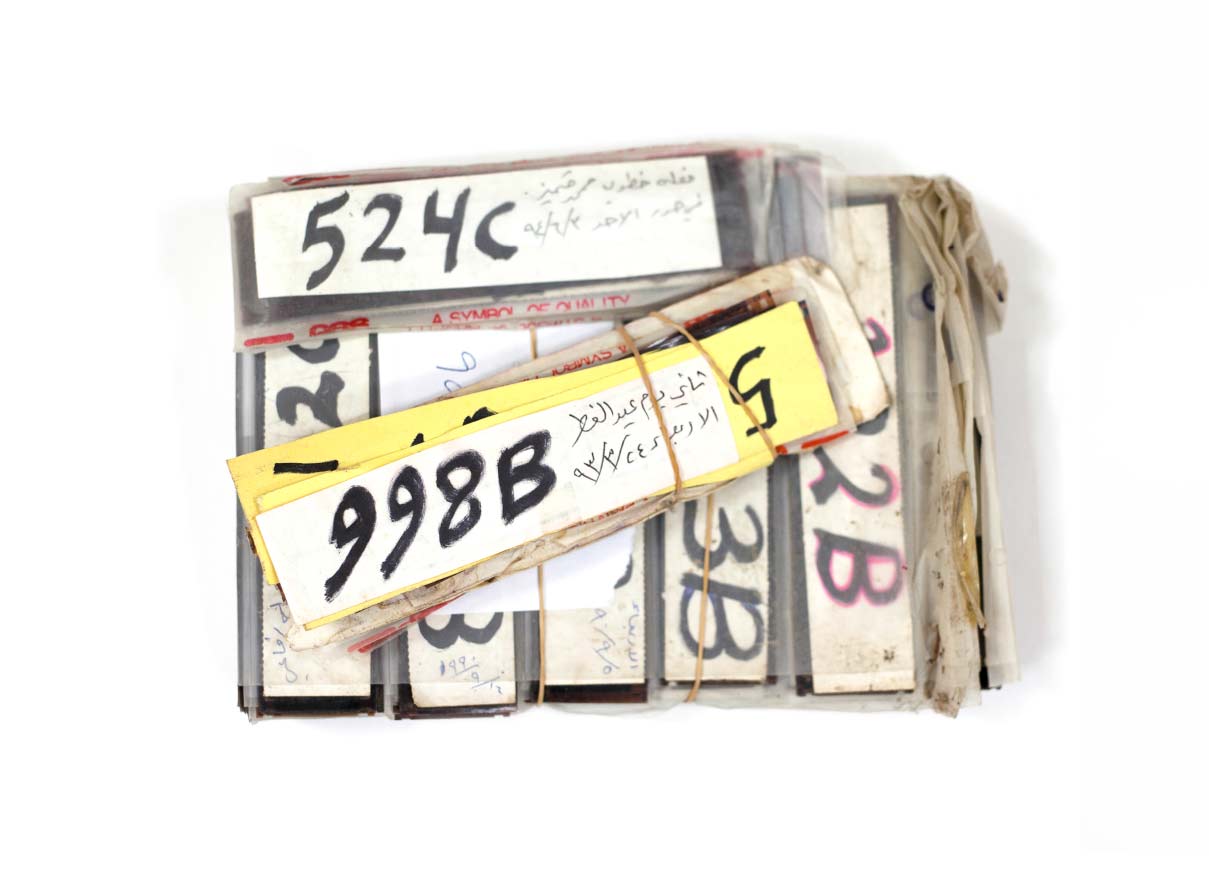

A group is a static collection of photographs without a structure or constructed movement. This is the way collections exist when they are in limbo, waiting to be processed. At the Arab Image Foundation, there are groups of photographs in boxes, binders, stacked, held together by a common denominator, such as topic, subject matter or provenance. The best example I have of a photobookwork that reflects this state of accumulation, what an unprocessed collection looks like at the Arab Image Foundation is Bayroumi (4,600 questions). In this case, a collection that is grouped by provenance and hasn’t been studied yet. All we know is that it is a collection of approximately 4600 negatives of 35mm format, packed in cardboard boxes and plastic bags, brought in by Arab Image Foundation founder Akram Zaatari, from the studio of Mohamad Bayroumi in Saida, Lebanon.

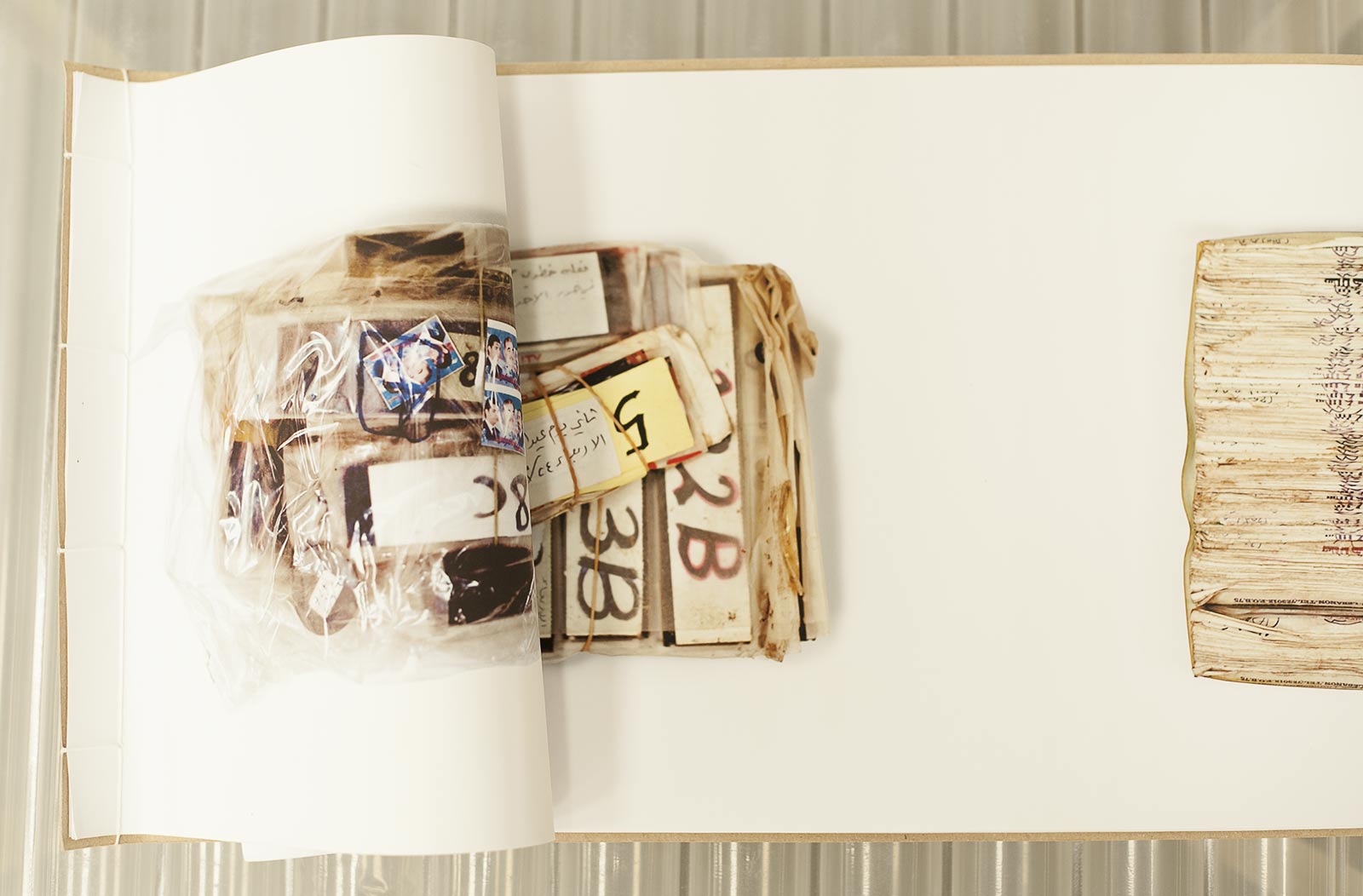

When I designed the book I asked myself how could I represent the collection in a state of accumulation, still being researched. It is a scroll book, with 10 photographs of films, negatives and contact prints in plastic bags, printed in seven pages with different lengths (30.5cm, 61cm and 92cm), stitched with Japanese stab binding and bound to a roll in an acrylic tube. The handwriting is by Charbel Saad, the collections’ manager. The work is printed with an Inkjet printer on Epson matt-coated paper and the cover is in card stock with a sticker, where the colophon is situated.

I used the scroll format that displays a succession of pages in a simultaneous tableau, allowing for a vision outside of the codex time. I introduced gaps in the unprocessed collection and this way each sack of contents starts to get individuality. It could be considered the beginning of a process of unraveling the life of Bayroumi studio.

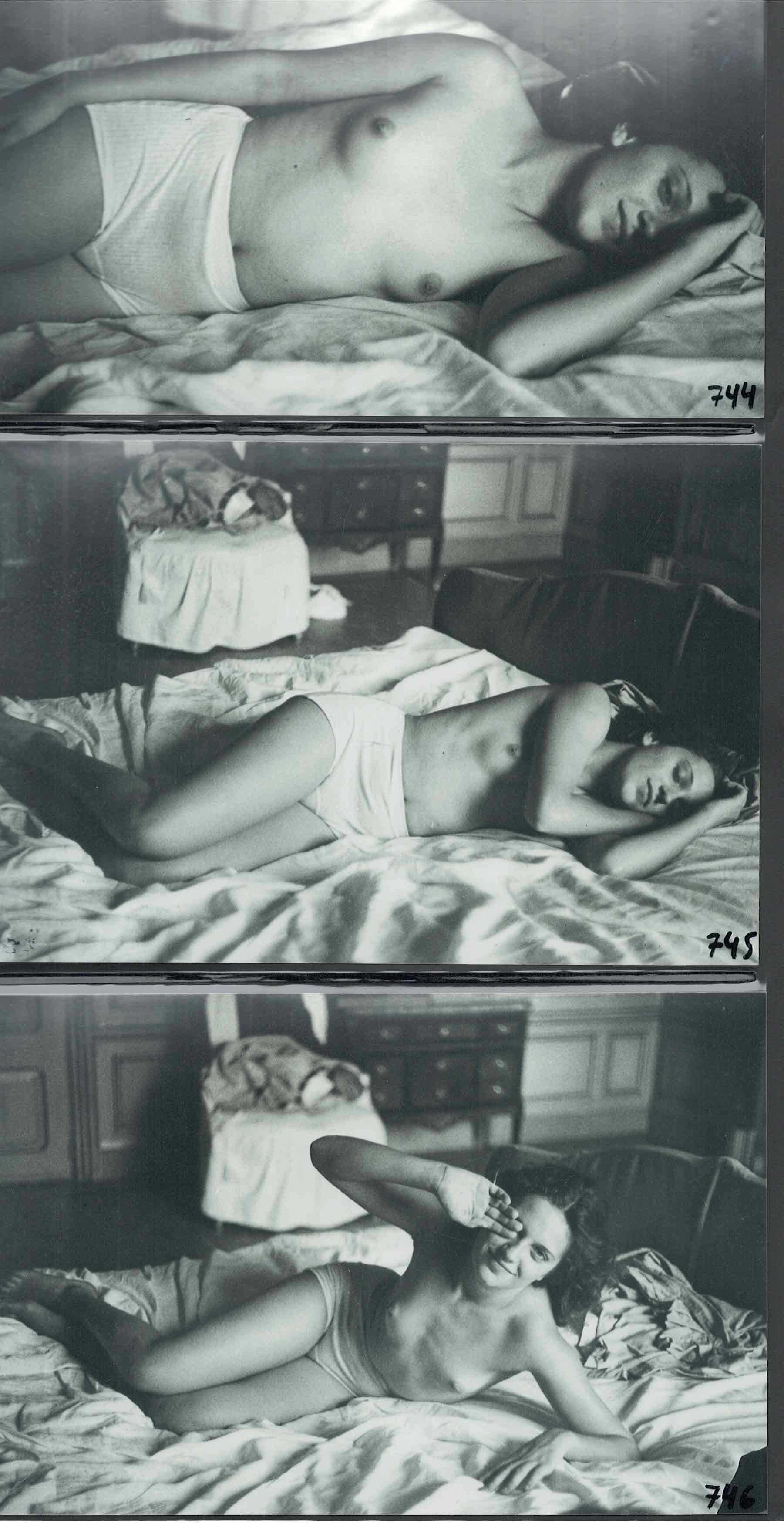

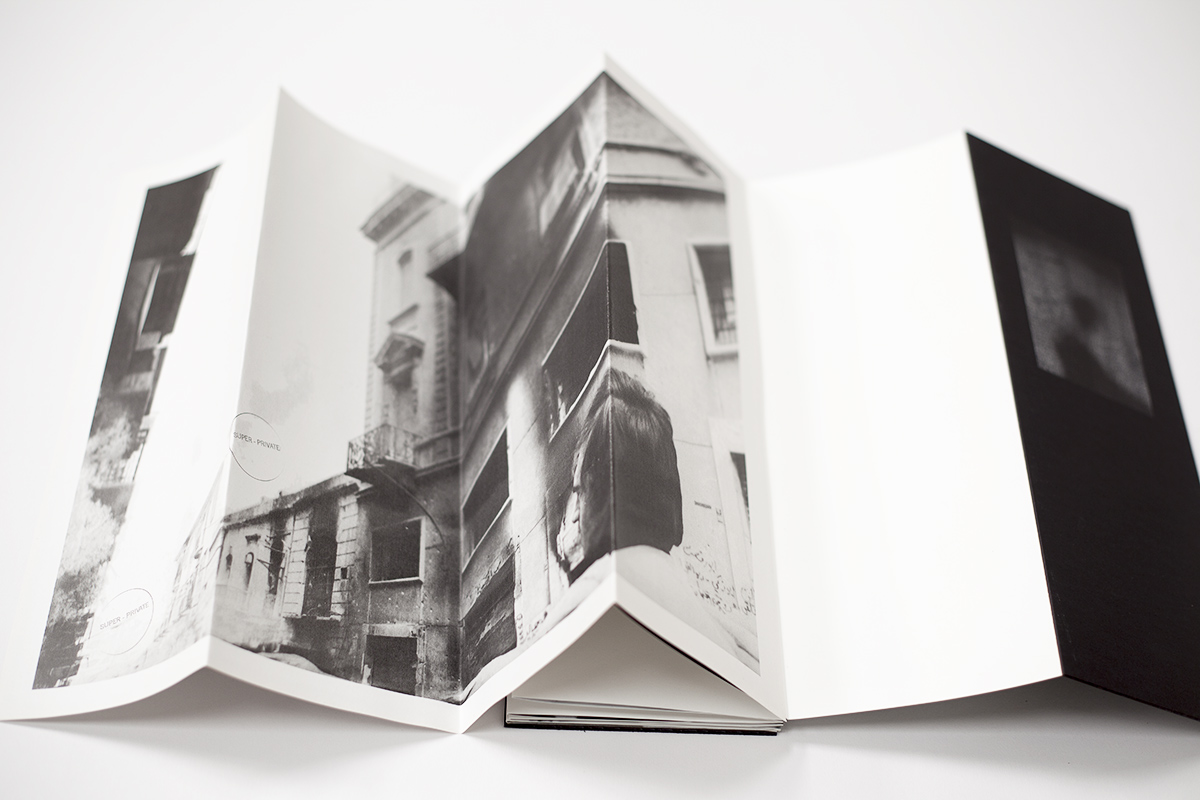

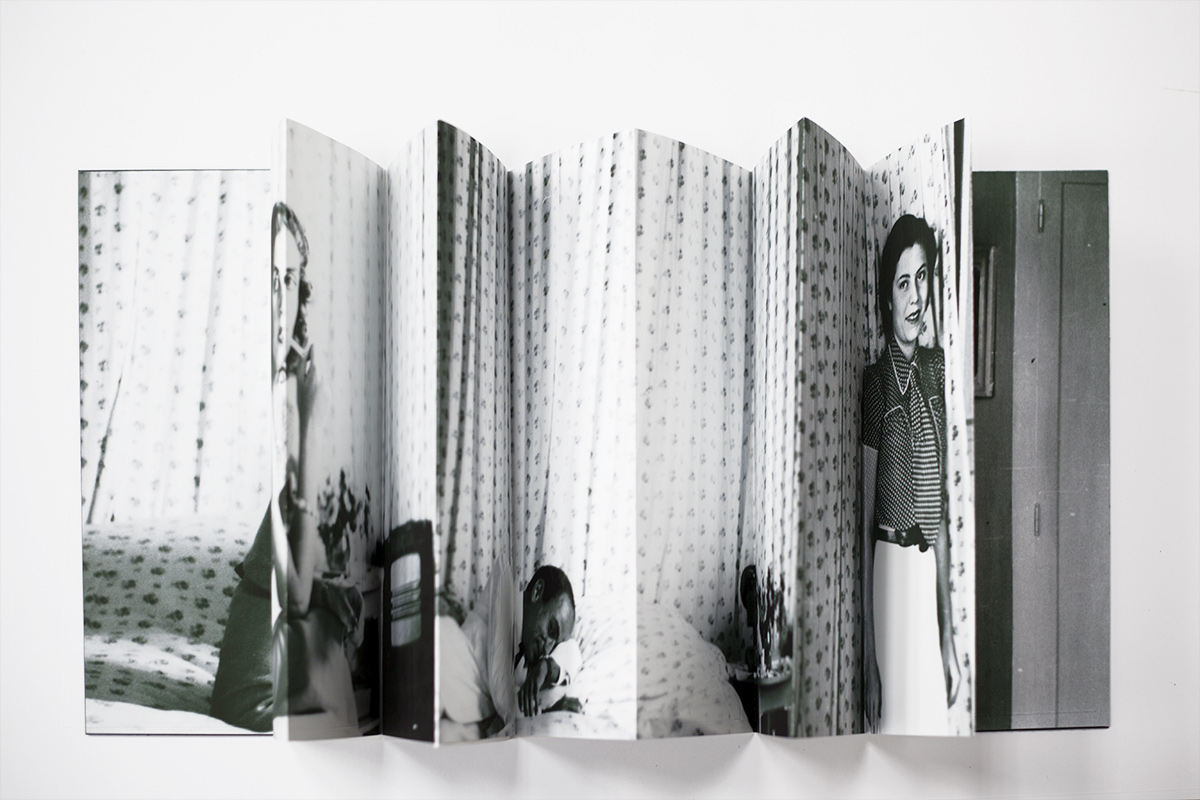

A series is when there is already some constructed movement. The series can link a number of photographs in a straight line, with a linear progression, each picture is an extension of the previous one, in a succession. One day I asked Hala Tawii, then librarian at Arab Image Foundation if she had any seedy … sexy…photographs, any collection troubling the archive that I could work with. She brought two ring binders labelled EPS collection, with A6 size prints. She didn’t know much about the photographs, just that something was not quite right and that I might like them. She also warned me that it was super private (she whispered her words) and they would have to contact the collection’s donor for approval. I made a mental note that should I be granted access, I would title the project Super-Private.

These binders contain hundreds of prints organised as a series, in the order of the date they were taken. The donor brought the films in, they were developed and printed to a standard family album size, he was asked to identify dates, location, and names and a spreadsheet was associated with the binders. Which remained in limbo until I arrived in Beirut, 10 years later.

My initial engagement with the box was to select some of the scenes, order them around significant moments, and use the series as a departure point to construct a more complex organisation, a sequence where several photographs react to one other, but not necessarily with just the adjacent photograph.

2. The story-showing technique

The second anchor in my practice with photographs collections is to sequence them by adding context. I call this the story-showing technique, because in the book form, it is possible to show the photographs alongside research, creating a hybrid association of photographs with each other and external documents that opens narrative possibilities. The photographs become an index to a larger narrative that research and design can uncover through documentary fieldwork, interview, oral history, biography and auto-biography.

This bio-political approach, gives depth to the work and allows the reader to know me and the subjects in the photographs. It is here that I connect with the documentary tradition of photobook publishing. In the 1970s photographers introduced the term ‘photobook’ as photographic documentary artwork in the book form, made possible by affordable printing. 7

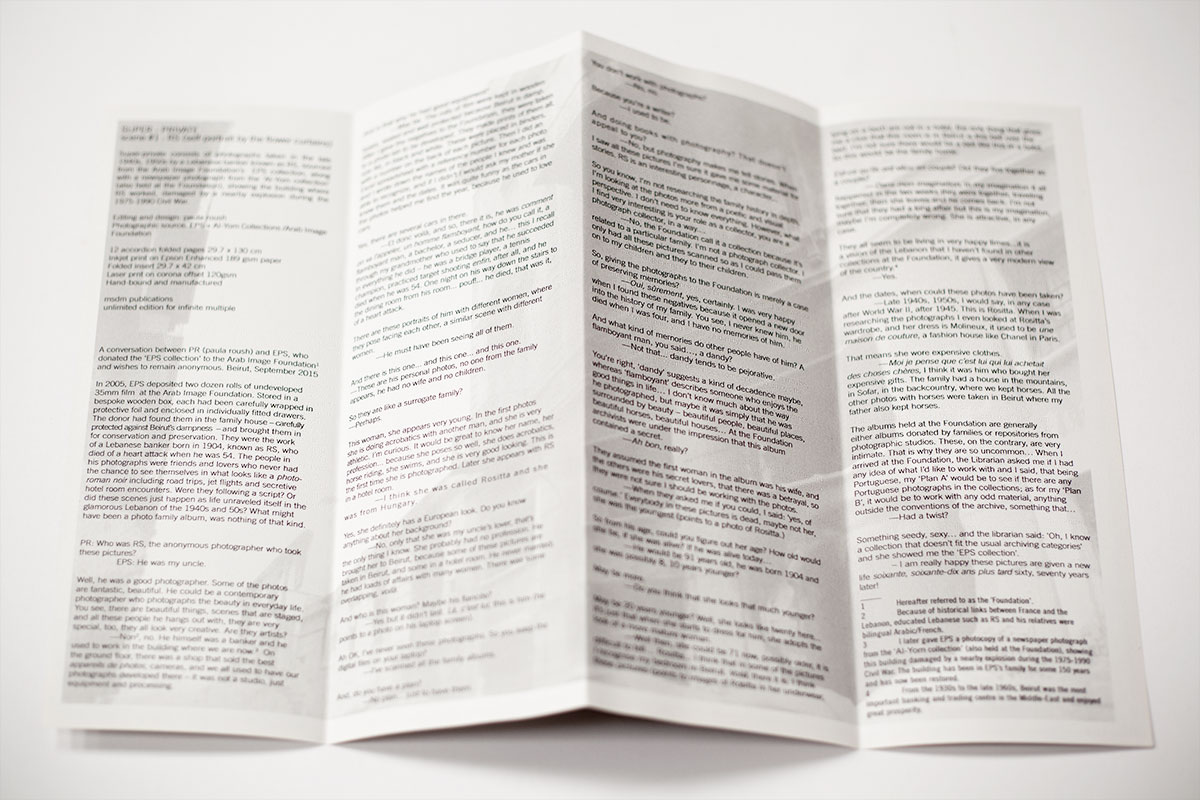

Back to the super private binders… The collection’s donor, EPS was indeed a very private person, and asked me to use solely initials for both his name and the photographer’s name, his uncle RS. But he was thrilled I was interested in the uncle’s photographs and gave me full permission to create. We met in the family building, where he works, and where his uncle also worked at the time he photographed. I interviewed him with the idea to integrate this text in the book in the form of an insert.

I had with me all the book dummies of my research at the Arab Image Foundation, and he saw a photo where he recognized the building where his uncle worked. A photo he had never seen but was part of the Al-Yom collection (more about this collection below) and showed the building just after the civil war, half-destroyed, and so I combined this photo with his interview. The insert, brings together two collections EPS and Al-Yom that were previously separated.

Group and series is the organisational logic of the archive, where there is no difference, no individuality, and no context. The desire for conservation levels all documents when they are grouped in boxes, organised by place or date. The rational model has an impersonal effect, all photographs are equally important and equally banal, their individuality is lost; sequencing offers an opposition, a challenge to the dominant models of the archive, which are the group and the series.8

This sequencing strategy is about tuning in with the material energy of the collection, as well practicing what is known as archaeologies of the contemporary past.9 Publishing as archaeological investigation of traces and presence of the past in visual culture, can provide a significant new dimension to the understanding and interpretation of place and the everyday.

3. The photo-text authorial position

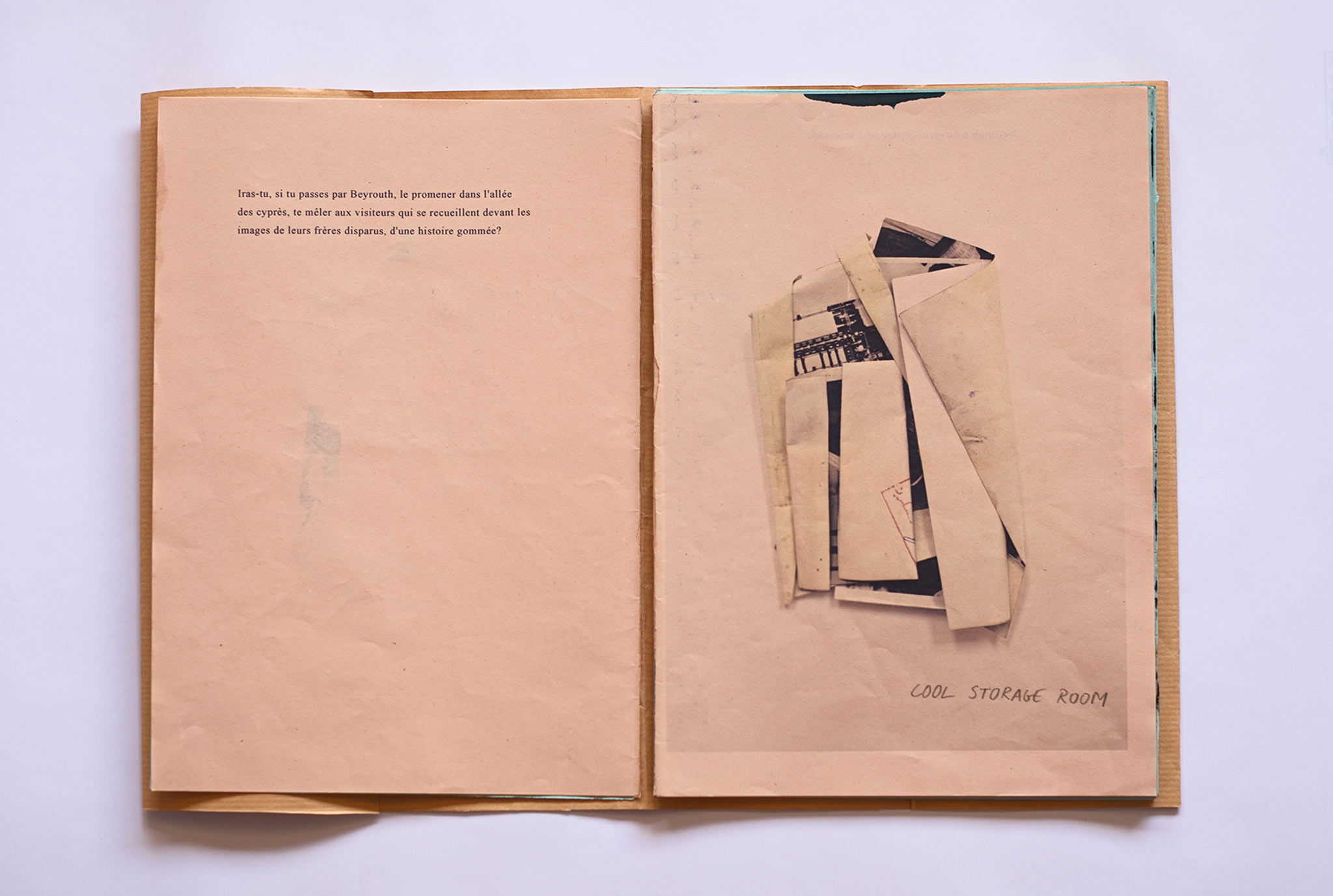

The photo-text is a blending of photography and text that investigates the relationship between image and writing. At the Arab Image Foundation, I found several storage boxes labelled Al-Yom. There was little information available about the provenance of the photographs and there was an additional challenge: these photographs were torn, folded, curled, a working term used at the Arab Image Foundation to categorise heavily damaged photographs that require special care in storage and preservation.

It involved several weeks of phone calls and emails to find more about the photographs. Al-Yom had been an Arabic-language daily newspaper published in Lebanon, no longer in print. The collection was brought in by Arab Image Foundation’s former director Zeina Arida who found it outside Walid El Tibi’s apartment, after the newspaper’s editor passed away and the apartment where he lived was cleared out. Al-Yom was founded by Afif El Tibi, the father of Lebanese journalism in 1937 and closed when the newspaper was attacked at the outbreak of war in 1975: armed militia stormed the building and gave the staff thirty minutes to leave the offices.

I started experimenting with book design pairing the damaged photographs with text sampled from A L’ombre D’une Ville, a 1993 book by Beirut-based writer Elie-Pierre Sabbagh. I sampled all the sentences with the word Beirut in it and was given permission to repurpose the text in an unbound bookwork, 47 pages A4 size, each photograph at the recto (right side of the folio) paired with a sentence at the verso (folio’s left side). The bookwork was laser printed on coloured paper and organised in a folder labeled with stickers. I think of Al-Yom’s photo-textuality in this way: the photographs are the referential blocks of the work, the text blocks introduce temporal dissonance, separating the photographs from their own temporality and placing them in relation with the novel but still at a distance. This interaction between photos and text opens a field of visual and textual possibilities, where the text is there not to explain the photographs but as reference points that interlock with the photographs to create an itinerary. The text from the novel is itself a work of auto-fiction, and when it collides with the photographs they collaborate in a real-fictional object: are the photographs documenting Beirut in the text? Or is the text fictionalising the reality imprinted in the photographs?

4. The haptic mode

Developing the haptic mode is taking the book content and giving it a material experience. Its like taking photos from a flat drawer or archive folder, into an experience of touch that engages the senses. It’s how we use our layout and binding to make more meaningful and impactful sequences, where we use the three-dimensional experience of the book to show the story. There is an integration of all material elements of the book, it’s not just the content but the space and time of the reading experience.

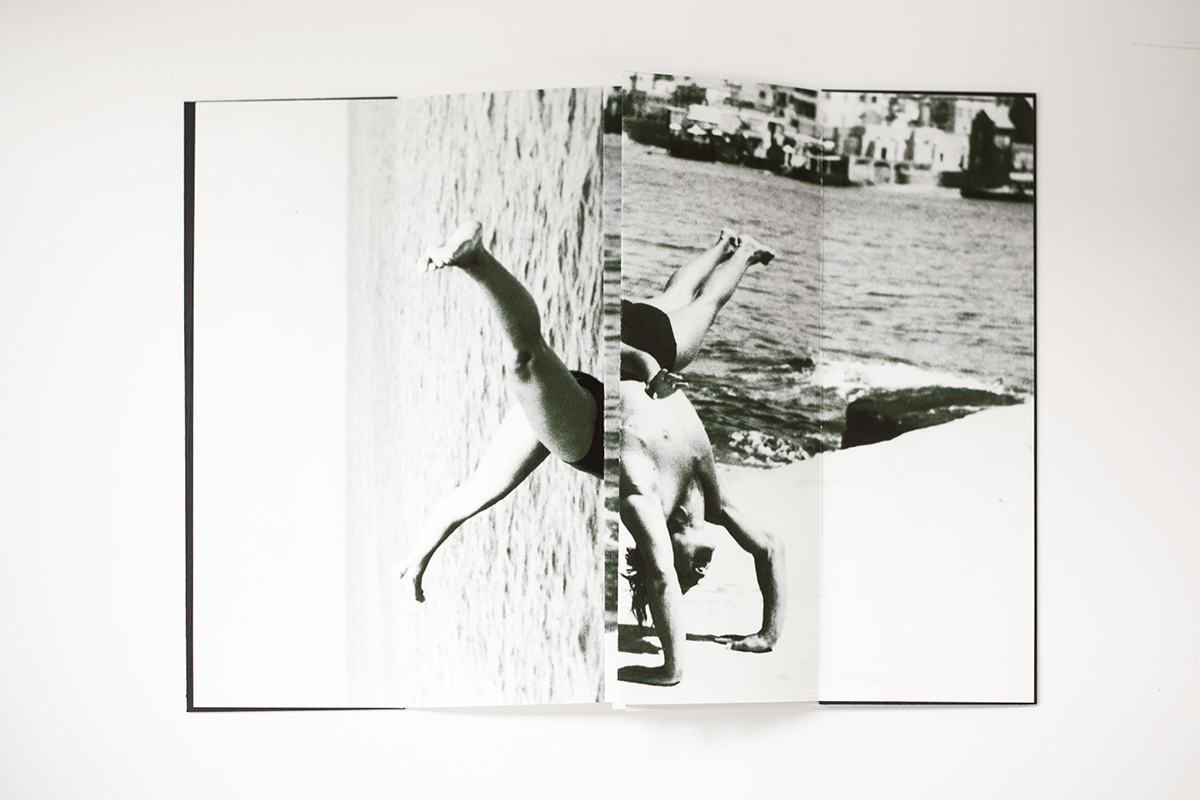

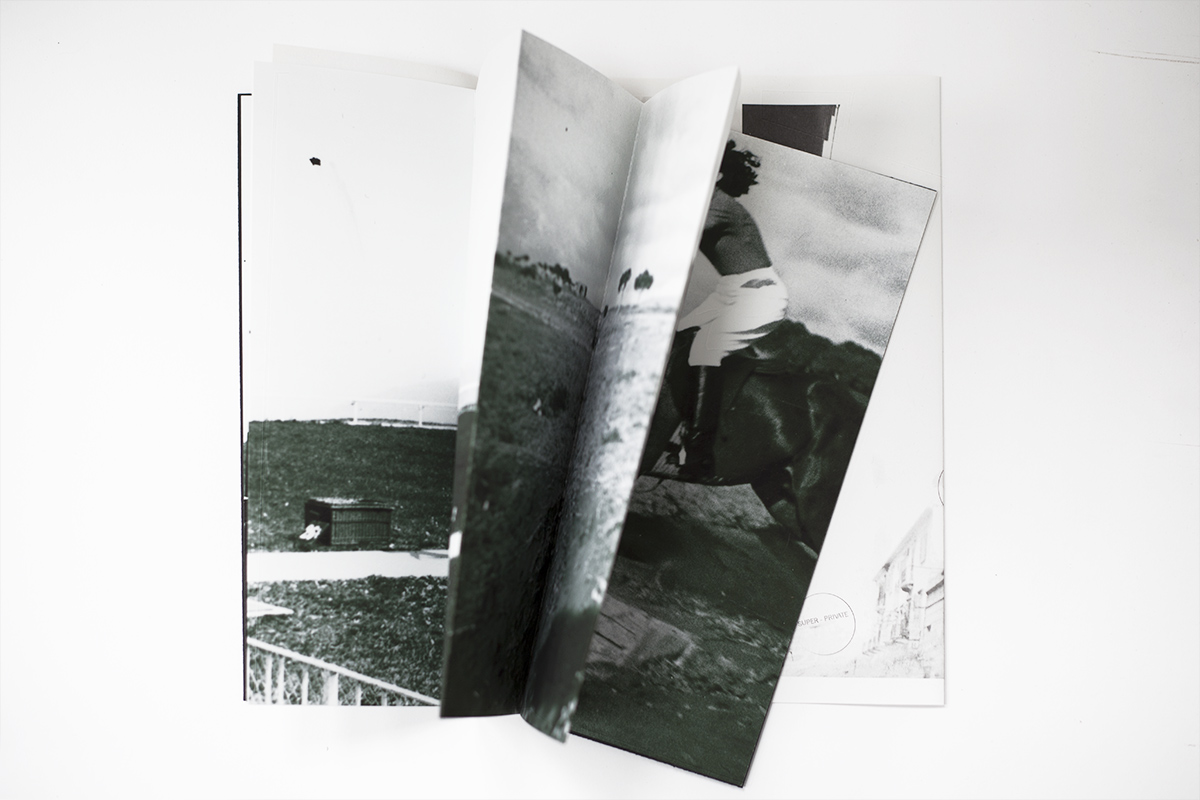

A good example is Super Private where we can see this principle in action. In the hardcover edition, printed with inkjet on coated matt paper, I used several gatefolds, that extend the size of the page when opened, This encourages the perception and manipulation of the book object, using the senses of touch and proprioception connected to the position and movement of the body. In the leporello editions, single scenes are collaged in a way that the folding and unfolding of the pages uncovers unseen details or perspectives of the scenes.

The haptic mode is something that develops through practice. It’s ‘a muscle’ that as a photobook designer we need to exercise. It comes from the desire to create a photobookwork, which is not the same as a photography book or a book of photographs due to its activation of the book medium. In the 1980s, the term photobookwork related this to the field of artists’ books and a category of contemporary art production and alternative exhibition space. 10 This is expanded in 21st century, when photobookwork is seen as a publishing medium that takes the combination of photography, text and the physical activation of the book to another level, and creates a hybrid mode of representation combining photographs, text and publishing practice. 11

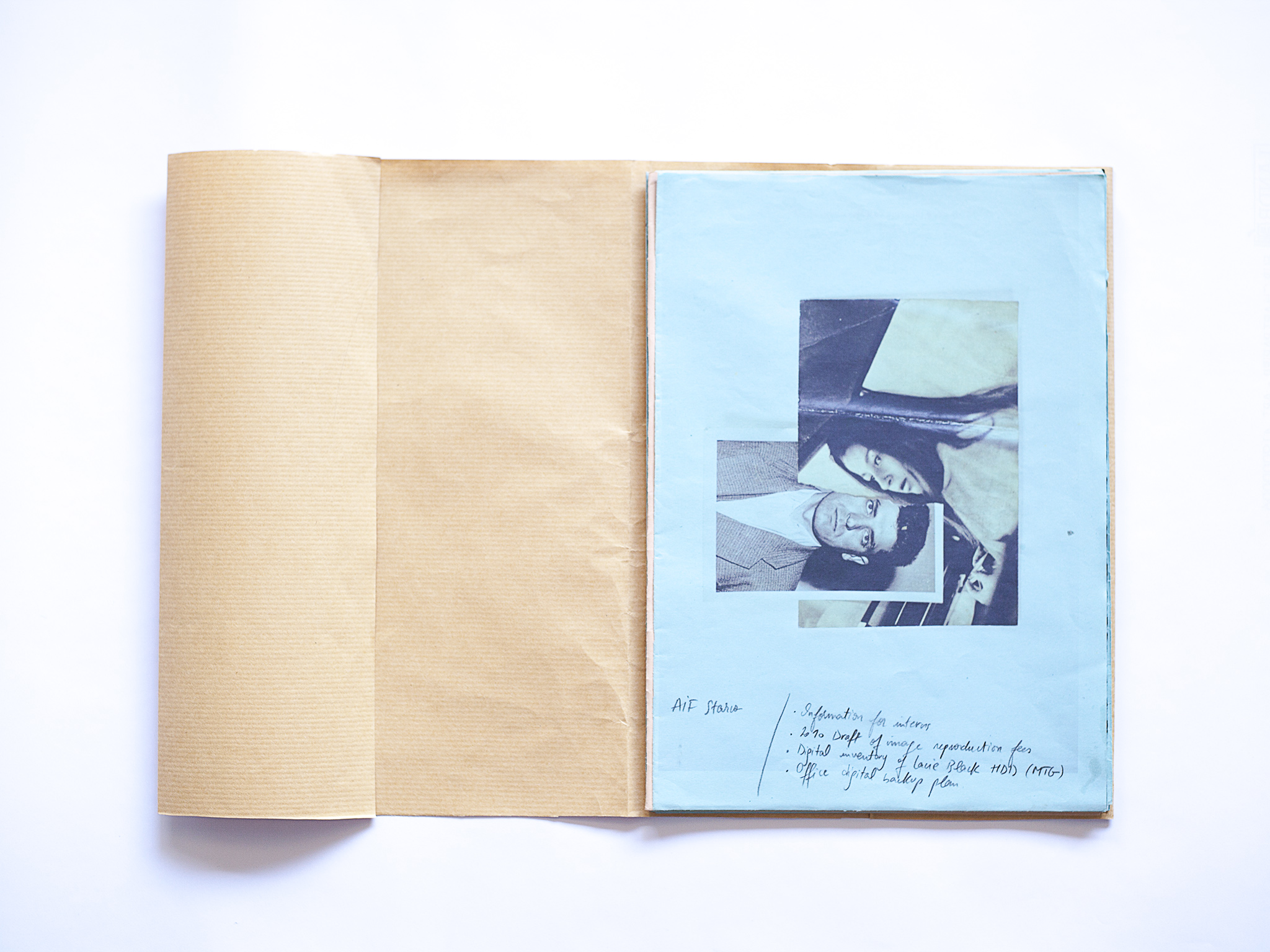

5. The book-dummy

The photobook dummy is a visual thinking tool, and next to the content itself, the photobook dummy is the most important aspect of delivering the project, it is the “photobook-to-be.” 12 It is the physical materialisation of the project, in that it allows us to organize the groups, series and sequences and draw the readers into our photographic and textual message, all while creating a haptic experiential involvement that resonates with them.

In my practice, the book dummy provides a visual structure, to develop a story, flexible enough to decide what to use and leave out, what is doable within the material constraints of the project, i.e. the printing and binding options available. It is a process in which I imagine the book as if it has already been published, I can hold the dummy in my hands, place it in a table, open the cover, feel its weight and the hands flipping through the pages.

I like to think that my research at the Arab Image Foundation was solid, that it added value and was powerful but I can tell you with one thousand per cent certainty that the strongest component of the work that provided me with the opportunity to work, publish and exhibit so quickly was my ability to create powerful book dummies. I honed this skill because when I work with photo archives, archivists, families and owners of photographic collections, I need to show them my selection, what I’m planning to publish, and let them know that I actually care. At the Arab Image Foundation, I used the book dummies to share the process with the archivist, the collections manager, and the family members I interviewed for research. When I visited PlanBey, the Beirut based photobook editor and bookshop, I showed the book dummies to their creative director Tony Sfeir. He liked what he saw and that’s why he invited me to publish with him and exhibit the editions at their Makan Space in September 2015.

In summary:

1: it’s about handling a collection, the ability to work with a large number of photographs,

understand the difference between groups, series and sequences,

2: find the relevant context by bringing in fragments of the contemporary past,

contruct links between photographs and research, and challenge the rational logic of the archive

3: encourage touch and the feeling of active involvement through page size, folds and materiality of the book

4: mix photographs and text/ typography in an unexpected way to create a phototext

that challenges the perceived vision of a book of photographs is

5: start with the dummy from day one, and review it daily to envision the project

as a 3-d artwork and communicate with people around us.

If you have any project in hands that you’d like to show me, feel free to email me.13

Remember the Found Photo Foundation is also open to collaborations. I hope you found value in this presentation. I know that if you implement these key teachings you will be able to develop a powerful photobook practice. Good luck!

1 Order and Collapse: The Lives of Archives International Photography Symposium Valand Academy in collaboration with the Hasselblad Foundation, Valand Academy, University of Gothenburg, Faculty of Fine, Applied and Performing Arts, October 15 -16 2014

2 Dear Aby Warburg: What can be done with images? Dealing with Photographic Material, exhibition curated by Eva Schmidt, Museum für Gegenwartskunst Siegen, December 2 2012- March 3 2013;and Paradigm Store, exhibition curated by HS Projects, 5 Howick Place, London, September 25 – November 5, 2014

3 such as Flora McCallica, photobookwork with collage of orphan photos sourced from the Found Photo Foundation.

4 I narrated this story in paula roush, Chaos of memories- Surviving archives and the ruins of history according to the found photo foundation. In G. Knape, N. Östlind, L. Wolthers &T . Martinsson (eds) Order and Collapse: The Lives of Archives. Art & Theory, Stockholm 2016

5 This process finds resonance in the research of other artists, such as Rebecca Fortnum, organizer of On Not Knowing; How Artists Think Symposium, Kettle’s Yard nd University of Cambridge, 29 June 2009

6 I follow the concepts and terminology shared in Keith Smith, Structure of the Visual Book, Keith Smith Books, Rochester 2003

7 Research into photobook publishing reveals historical precedents such as Bill Owens, 1979 Publish your photo book: a guide to self-publishing, and Thomas Dungan, 1979 Photography between covers: interviews with photo-bookmakers. Referenced in Paulo Silveira, 2015 A Faceta Travestida Do Livro Fotográfico, 24o Encontro da ANPAP Compartilhamentos na Arte: Redes e Conexoes

8 This approach is inspired by Allan Sekula practice and writing, namely the essay On the Invention of Photographic Meaning,Artforum 13, no. 2 (January 1975): 36–45

9 I follow the concept and terminology put forward in Victor Buchli, Gavin Lucas 2002 Archaeologies of the Contemporary Past. London: Routledge

10 I adopt the term photobookwork coined by Alex Sweetman. See Alex Sweetman (1985), Photobookworks: the critical realist tradition, in Joan Lyons (ed) Artists’ books: a critical anthology and sourcebook. Rochester, N.Y. : Visual Studies Workshop Press.

11 I follow here the analysis of current photobook publishing practice in Gregory J. Harris, 2010 Photography By the Book: Wall, Matta-Clark and the Photobook After Ruscha. A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Art History, Theory, and Criticism The School of the Art Institute of Chicago

12 Foam Magazine Issue #34 Dummy Spring 2013

13 My updated contact is always available at msdm studio’s website: msdm.org.uk