Chaos of Memories:

Surviving Archives and the Ruins of History

According to the Found Photo Foundation

In

Order and Collapse: The Lives of Archives.

Editors: Gunilla Knape, Louise Wolthers,

Niclas Östlind

192 pp., Bi-lingual English and Swedish

Published by: Photography at Valand Academy,

University of Gothenburg/ Hasselblad Foundation

and Art and Theory Publishing, 2016

ISBN 9789188031020

Order and Collapse Lives of Archives

Conference, University of Gothenburg 2015

For more information on

Order and Collapse see here.

See the Found Photo Foundation here

Full essay here

Excerpts [pdf]

The text "Chaos of Memories: Surviving Archives and the Ruins of History According to the Found Photo Foundation" is an essay by paula roush that discusses the work of the Found Photo Foundation (FPF) in the context of contemporary archival practices.

Key Themes and Content

FPF as an Experimental Archive: The essay focuses on the Found Photo Foundation as an experimental archive of "orphan" photographs that have lost their provenance or ownership, such as those found in the garbage or in second-hand markets.

Challenging Traditional Archives: It challenges the rational logic and authoritarian use of conventional archives, which typically rely on strict provenance and classification systems. The FPF instead mobilizes vernacular and queer feminist models of the archive to document often invisible lives and stories.

Memory and Identity: roush describes how the loss of her own childhood photographs was a "distressing" experience, leading to a feeling of a "gap in [her] biography". The subsequent creation of the FPF became a method to retroactively "recapture [her] past and that of [her] country" by using fragments of others' lives and childhoods to fill that void.

Archival Art Practices: The text examines how archival theory and practice challenge each other through specific artistic projects and exhibitions, such as "Dear Aby Warburg" and "The past persists in the present in the form of a dream". These projects use various media and methodologies, including provisional taxonomies and participatory tools, to explore how photographic collections are used in contemporary art.

Publication Context: The essay is published as a chapter in the anthology Order and Collapse: The Lives of Archives, which explores the impact of digital technology and increased data on archives today, and features other texts and artworks that represent contemporary artistic approaches to existing and new archives.

Chaos of Memories: Surviving Archives and the Ruins of History

According to the Found Photo Foundation

text by paula roush

[intro]

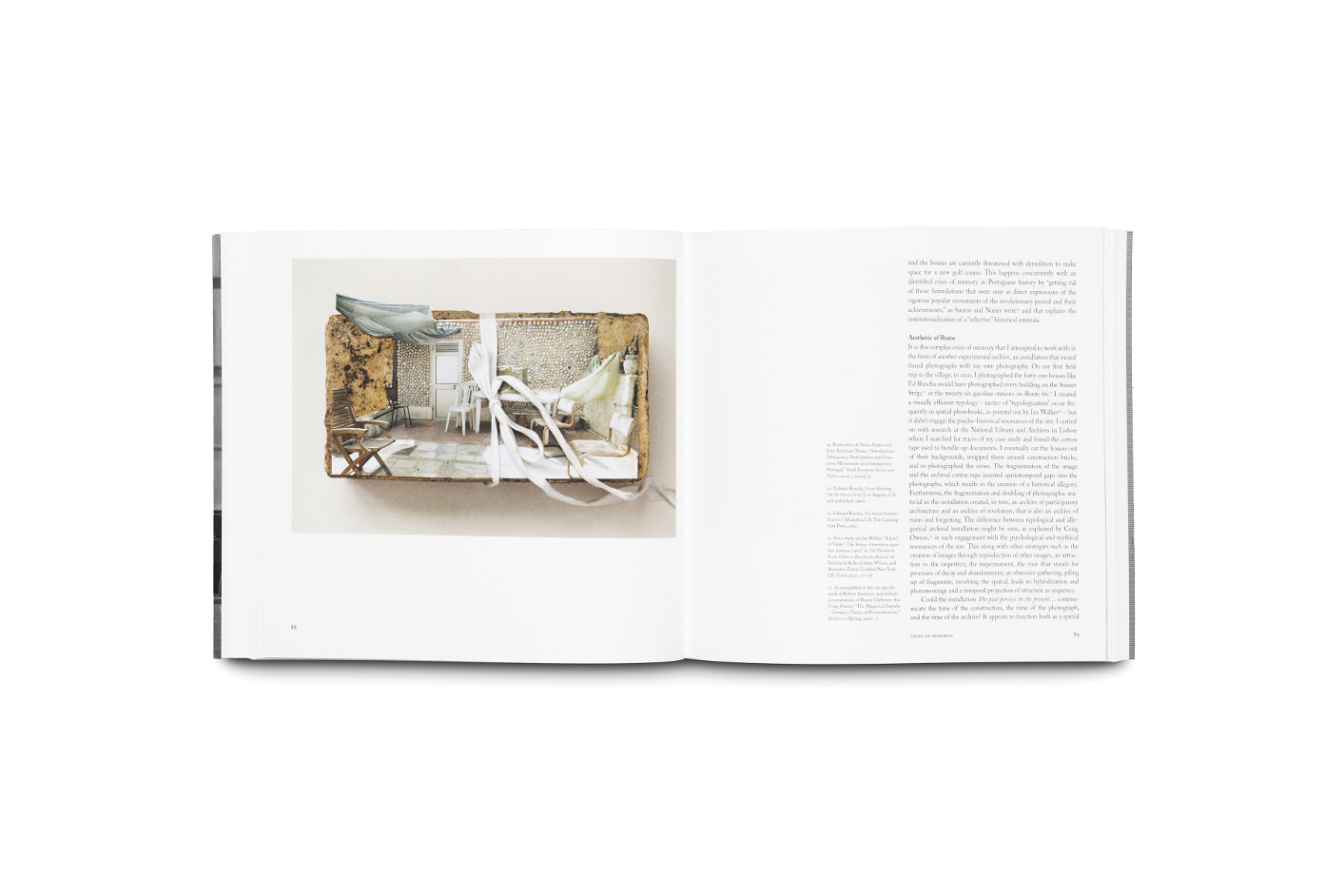

Most archival artworks that circulate today in exhibitions and publications investigate the archive as the site of an ongoing negotiation between the appropriation of photo-historical material and accumulative strategies of installation and publication. To date such research has produced several curatorial projects where strategies of photographic reproduction and distribution are scrutinised as particular modes of knowledge production that whilst engaged in the creation of archival art are far apart from the 19th century model of bureaucratic archive.1

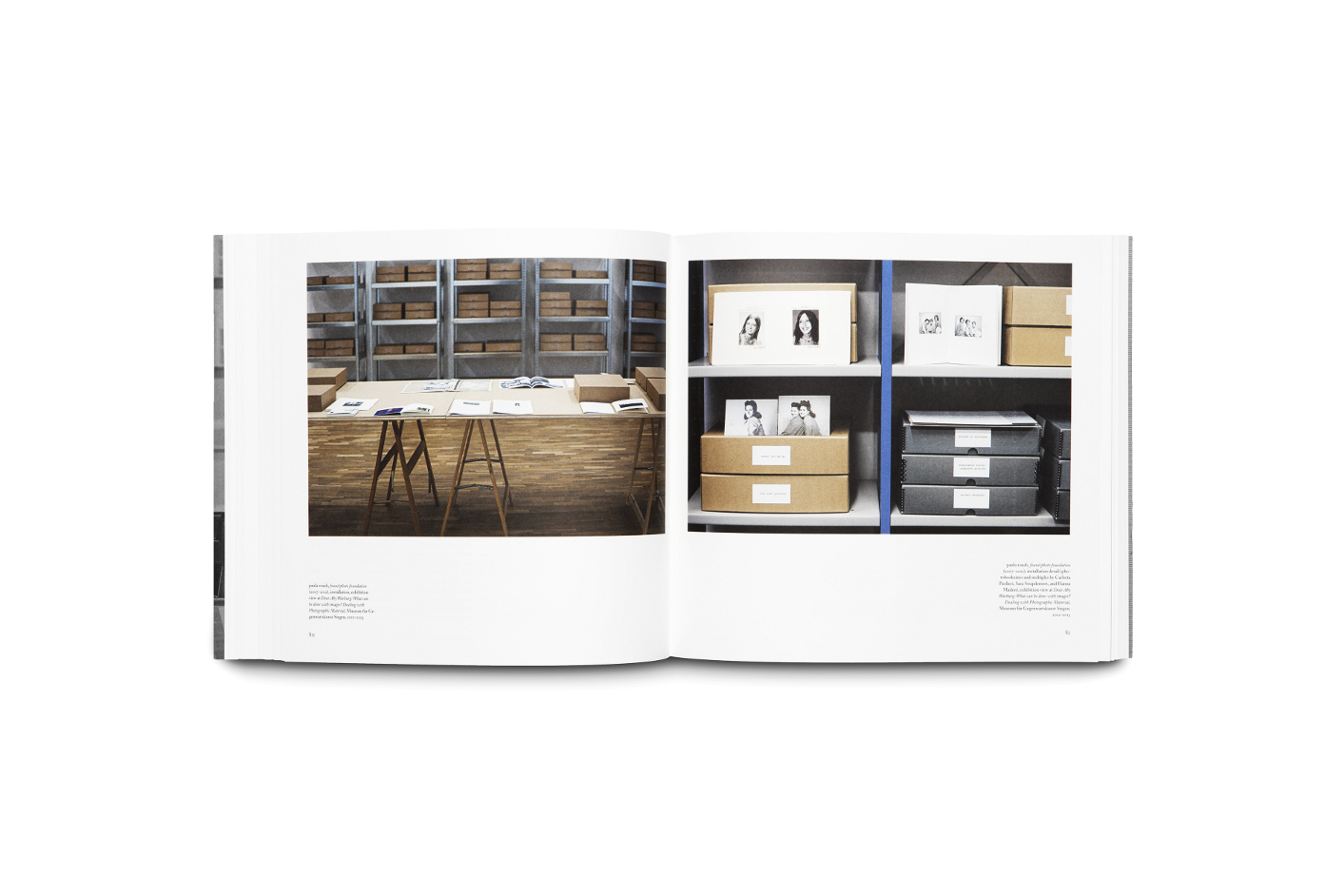

Such is the case with the exhibition Dear Aby Warburg: What can be done with images? Dealing with Photographic Material (2012), 2 where my project found photo foundation (fpfoundation)3 was exhibited as an experimental archive. This and the other works installed across the vast museum explored the many configurations of the use of photographic collections in contemporary art, and its many transmutations since Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas (1924-1929).

The homage to art-historian Aby Warburg (1866 - 1929) as precursor to current art archival practices is unpacked by the exhibition’s curator Eva Schmidt, in the accompanying research publication.4

The montage of reproduced photographs from divergent sources, the use of variable, nonsystematic ordering parameters, and the extremely provisional display strategies are some of the Mnemosyne Atlas’ characteristics that reappear in contemporary works in the exhibition, side by side with the processes of photographic collection, accumulation and archiving I used in the fpfoundation.

The genesis of the photographic collections in the exhibition can be connected to the paradigm of time identified by George Didi-Huberman in Warburg’s method of photo reproduction and montage developed in the Atlas.5 Warburg’s ‘iconology of the interval’ results from thinking about time itself as a montage of heterogeneous elements, and memory as an editing process that separates fragments, produces holes in the historical timeline and field intervals.

It is then a question of selection, of movement between storage (the archive) and presentation (the atlas), as theorist Ludwig Seyfarth wrote: ‘The artists of the exhibition Dear Aby Warburg are collectors of images; their artistic individuality consists less in a style or gesture than in the specific manner in which they...also physically open up new spaces for thinking between the images- something begun with Warburg when he started to pin photos to canvasses." 6

In the case of my photographic collections, many of which were found in portuguese second hand markets - "…It is usually impossible to trace the provenance of these photographs [referred] to as 'orphans'... They have become homeless, but nonetheless tell something like a private subterranean history of the time spent under a dictatorship.”7 - there is an additional ethnographic potential, a relation to the real through documentary and fiction that opens up different ways of representing culture.

Due to my origins in a southern-european country, at the periphery of the art world canon, it is useful to extend here a reference to Catherine Russell’s study of ‘experimental ethnographies,’ practiced by artists whose works reflect on their cultures of origin. The editing of used, fragmented, even corrupted found imagery in collage, montage or archival practice creates “an aesthetic of ruins; its intertextuality is always an allegory of history, a montage of memory traces by which the artist engages with the past through recall, retrieving and recycling.” 8

Whilst the author’s main concern is with found footage, she extends her argument to found photography. Additionally, when living away from one’s country of origin, as it is in my case, the identity constructed with found images borders into that of an auto-ethnography. In this ‘journey of the self,’ the condition of being an orphan and homeless is in fact appropriated as the hallmark both of the fpfoundation’s collection and my own (photo)biography.

1 The development of the 19th century archive is analysed in depth in Sven Spieker, The Big Archive: Art From Bureaucracy (Cambridge MA/ London: The MIT press, 2008)

2 Eva Schmidt, Dear Aby Warburg: What can be done with images? Dealing with Photographic

Material, Museum für Gegenwartskunst Siegen, Siegen, December 2, 2012–March 3, 2013. Other curatorial projects linking contemporary art photo collections to the Mnemosyne Atlas include: Georges Didi-Huberman, Atlas. How to Carry the World on One’s Back?, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid 2010, Georges Didi-Huberman and Arno Gisinger, Nouvelles Histoires de Fantômes [New Ghost Stories], Palais de Tokyo February 4, 2014–September 07, 2014.

3 The found photo foundation will be referred to subsequently as fpfoundation, which is phonetically pronounced with an elongated f (2x)

4 Eva Schmidt, “Foreword and Acknowledgements,” In Dear Aby Warburg, what can be done withimages? Dealing with photographic Material, ed. Eva Schmidt and Ines Ruttinger (Siegen/ Heidelberg: Museum für Gegenwartskunst Siegen /Kehrer 2012), 11- 14

5 See Georges Didi-Huberman, L'image survivante– Histoire de l'art et temps des fantômes selon Aby Warburg, Paris: Editions de Minuit, 2002

6 Ludwig Seyfarth, “Space for thinking between the images: on the genesis of the 'photographic collection' as an artistic genre.” In Dear Aby Warburg, what can be done with images? Dealing with photographic Material, 33.

7 ibid

8 Catherine Russell, Experimental ethnography The work of film in the age of video (Durham / London: Duke University Press, 1999), p. 238

9 Sven Spieker, The Big Archive: Art From Bureaucracy, 4.

10 See http://msdm.org.uk

Chaos of memories

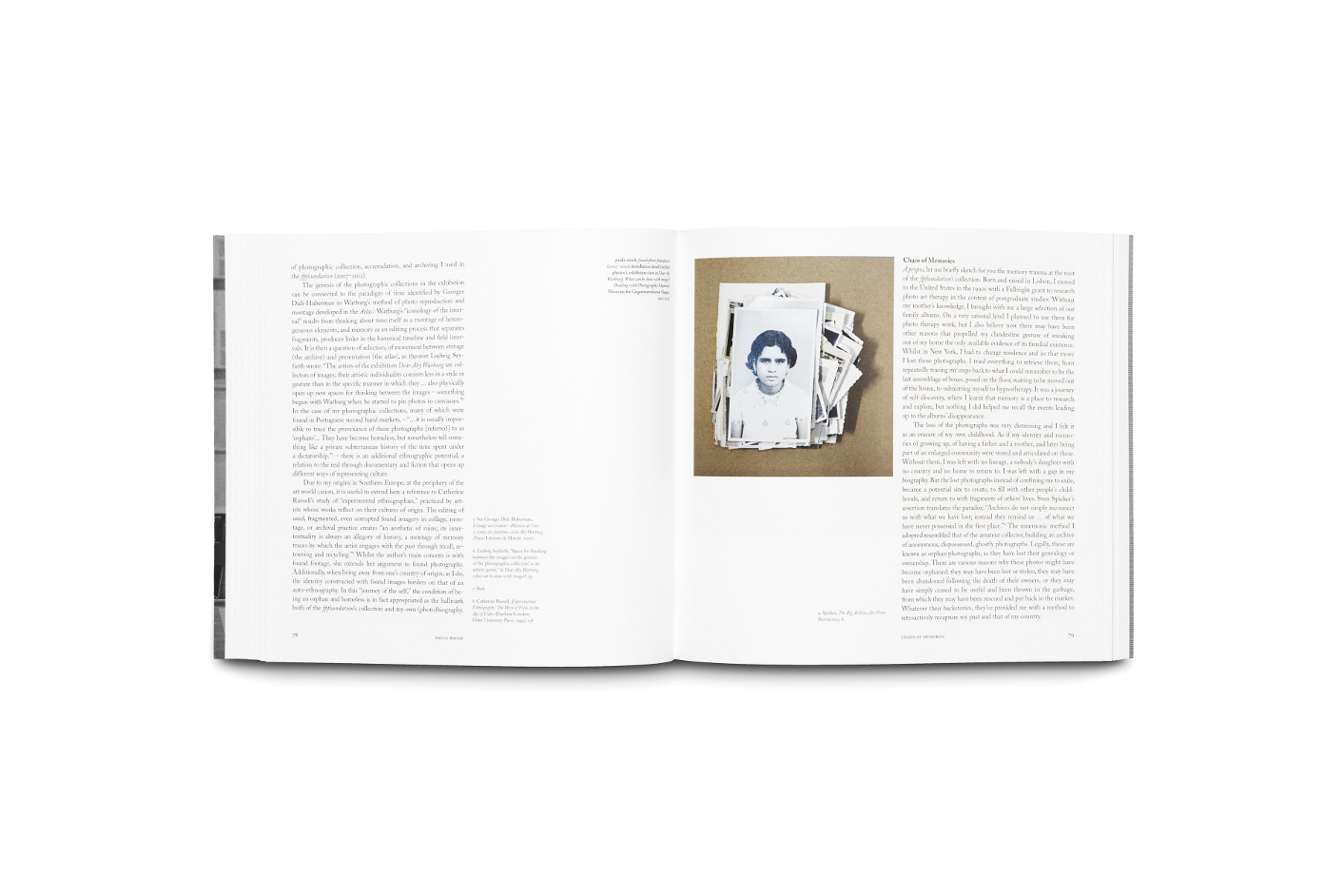

A propos, let me briefly sketch for you the memory trauma at the root of the fpfoundation’s collection. Born and raised in Lisbon I moved to the United States in the 1990s with a fulbright grant to research photo art therapy in the context of post-graduate studies. Without my mother’s knowledge I brought with me a large selection of our family albums. My reasons may have been multiple and at a very rational level, I planned to use it for photo therapy work; but I also believe now there may have been other reasons that propelled my clandestine gesture of sneaking out of my home the only available evidence of its familial existence. Whilst in New York, I had to change residence and in that move I lost those photographs. I tried everything to retrive them, from repeatedly tracing my steps back to what I could remember to be the last assemblage of boxes, posed on the floor, waiting to be moved out of the house, to submitting myself to hypnotherapy. It was a journey of self-discovery, where I learnt that memory is a place to research and explore but nothing I did helped me to recall the events leading to the albums’ disappearance.

The photographs’ loss was very distressing and I lived it as an erasure of my own childhood. As if my identity and memories of growing up, of having a father and a mother, and later being part of an enlarged community were stored and articulated on these. Without them, I was left with no lineage, a nobody’s daughter with no country and no home to return to. I was left with a gap in my biography. But the lost photographs instead of confining me to exile, became a potential site to create, to fulfill with other people’s childhoods, and return to with fragments of others’ lives. Sven Spieker’s assertion translates the paradox: “Archives do not simply reconnect us with what we have lost; instead they remind us…of what we have never possessed in the first place.” 9

The mnemonic method I adopted resembled that of the amateur collector, building an archive of anonymous, dispossessed, ghostly photographs. Legally, these are known as orphan photographs, as they have lost their genealogy or ownership. There are multiple reasons these photos might have become orphan: they may have been lost, stolen, they may have been abandoned following the death of their owners, or they may have simply ceased to be useful and thrown in the garbage, from which they may have been rescued and put back in the market. Whatever their backstories, they’ve provided me with a method to retroactively recapture my past and that of my country.

The fpfoundation grew thus as a framework for experimental archival practices, interested in the relationship between photography and memory. Its mission eventually developed into the ‘rescue of work produced by professional, amateur, and anonymous photographers found throughout the world,’ and represents now a vast collection of found photography. The fpfoundation’s status as an artist-led initiative is similar to other archival projects I developed throughout the years, to open up platforms for independent, self-sustainable collaborative projects. One of these, under the acronym msdm10 became the umbrella moniker for all my projects of ‘mobile strategies of display and mediation,’ which the fpfoundation belongs to.

Without an established agenda or a systematic program to enable independent fundraising and sustain a policy of acquisitions, publications and exhibitions, the fpfoundation has advanced in an opportunistic and parasitic way, in response to my own life-art practice. In terms of acquisitions, these result from my regular travel between London and Lisbon, and so there is a focus in photographic objects that were found and acquired in flea markets and car boot sales from Portugal and the UK. In addition, my determination not to miss a street market sale in every city I visit has added photos from all over the world, with the add-on of occasional photographic items gleaned from the streets where I often find discarded and defaced photographs, sometimes in advanced state of decomposition waiting for my adoption.

READ MORE [Part I] on experimental archives here