Paradigm Store

Curated by HS Projects

With: Ulla von Brandenburg, Cullinan & Richards, Kendell Geers, David Shrigley, Yutaka Sone, Maria Nepomuceno, Tobias Rehberger,paula roush, Claire Barclay, Elizabeth Neel, Simon Bedwell, Nike Savvas, Theo Stamatoyiannis, Anne Harild, Beatriz Milhazes

5 Howick Place, London

[press release] [artist's statement] [review: 3rd Dimension Magazine]

Historical allegories

The latest materialisation of the found photo foundation appeared in the installation The past persists in the present in the form of a dream (participatory architectures, archive, revolution) that was exhibited in London in 2014 by HS Projects as part of Paradigm Store, a curatorial project reflecting on the haunting gap between 20th century modernist utopias and historical matrixes that have ripped apart modernist myths of progress. The past… in the form of a dream occupied that gap between the 1970s promises of radical participatory democracy and the contemporary reality of neo-liberal democracy in southern europe, featuring the Apeadeiro housing estate, one of the urban villages developed during the portuguese SAAL architecture programme, and now facing demolition. I was a child in 1974 when the 25th of April coup d’etat put an end to five decades of fascist dictatorship. Within just a few months, the country underwent a fertile incubation period out of which mushroomed a series of experiments in participatory democracy with SAAL symbolising the architecture of the revolution.

Architect Jose Veloso built a SAAL project with a fishing community living in precarious conditions in a small shanty town in Meia Praia, by the seaside of Lagos city. With his team’s support the villagers formed an association and applied for funding and ownership of the land. Forty one houses were built following a ‘modular typology of evolutionary housing.’ The basic unit was the one bedroom flat, and each unit contained five additional options of interior organisation allowing the family to develop the space up to a five bedroom flat, according to their household needs. The architects made the proposals, elaborated the technical aspects of the construction and all decisions were taken in collective meetings, where almost everyone participated: “It was a very cohesive, lucid and coherent group in their decisions. They didn’t want each family to be simply building their own house. Instead, everyone worked in all the houses collectively, and they would all be built at the same time.” (1)

The SAAL programme was eventually dissolved in 1976 by a government invested in joining the prevailing neoliberal capitalist model, in a process of normalisation for the portuguese society where hegemonic models of western-style consensual democracy replaced the participatory experiments put in place during the revolution. The Apeadeiro village was never finished, the streets never paved and the houses are currently threatened with demolition to make space for a new golf course. This happens concurrently with an identified crisis of memory in portuguese history by “getting rid of those formulations that were seen as direct expressions of the vigorous popular movements of the revolutionary period and their achievements,” as Santos and Nunes write (2) and that explains the institutionalisation of a ‘selective’ historical amnesia.

Aesthetic of ruins

It is this complex crisis of memory that I attempted to work in the form of another experimental archive, an installation that mixed found photographs with my own photography. In my first field trip to the village, in 2010, I photographed the forty one houses like Ed Ruscha would have photographed every building on the Sunset Strip (3), or the twenty six gasoline stations on Route 66. (4)

I created a visually efficient typology, and tactics of ‘typologisation’ are frequent in many other spatial photobooks, as pointed by Ian Walker (5), but it didn’t engage the psycho-historical resonances of the site. I carried on with research at the National Library and Archives in Lisbon where I searched for traces of my case study and found the cotton tape used to bundle-up documents. I eventually cut the houses out of their backgrounds, wrapped them around construction bricks, and re-photographed the series. The fragmentation of the image and the archival cotton tape inserted spatio-temporal gaps in the photographs that result in the creation of a historical allegory. Further, the fragmentation and doubling of photographic material in the installation created, in turn, an archive of participatory architecture and an archive of revolution, that is also an archive of ruins and forgetting.

The difference between typological and allegorical archival installation might be seen, as explained by Craig Owens (6), in such engagement with the psychological and mythical resonances of the site. This along with other strategies as the creation of images through reproduction of other images, an attraction to the imperfect, the impermanent, the ruin that stands for process of decay and abandonment, an obsessive gathering, piling up of fragments, involving the spatial, leads to hybridisation and photomontage and a temporal projection of structure as sequence.

Could The past… in the form of a dream installation communicate the time of the construction, the time of the photograph and the time of the archive? It appears to function both as a spatial and a time montage that shifts the viewer’s perception between utopia, ruins, document and monument. The danger with ethnographic approaches is, according to James Cifford (7), the distancing of the represented communities in the ‘salvage paradigm’ that freezes them into a ‘present-becoming-past.’ This is something I have been very wary of, threading my way between documentary and experimental auto-ethnography. However, the allegorical structure of double representation, in which the ethnographing of the culture is recognised and made visible through photography’s reflexivity, complemented by the inclusion of other voices, transforms such ethnographic practices. Catherine Russell also sees this happening in the use of allegory to appropriate utopian desires, as in Walter Benjamin’s radical theory of memory. In her reading of Benjamin’s work, his study of the Paris arcades suggests that the past persists in the present in the form of a dream, often commodified as a wish image; this conception of the past is captured in the shifting temporalities of the reproduced and archived photography and became the title The past persists in the present in the form of a dream (participatory architectures, archive, revolution), for both a newspaper (8) and installation.

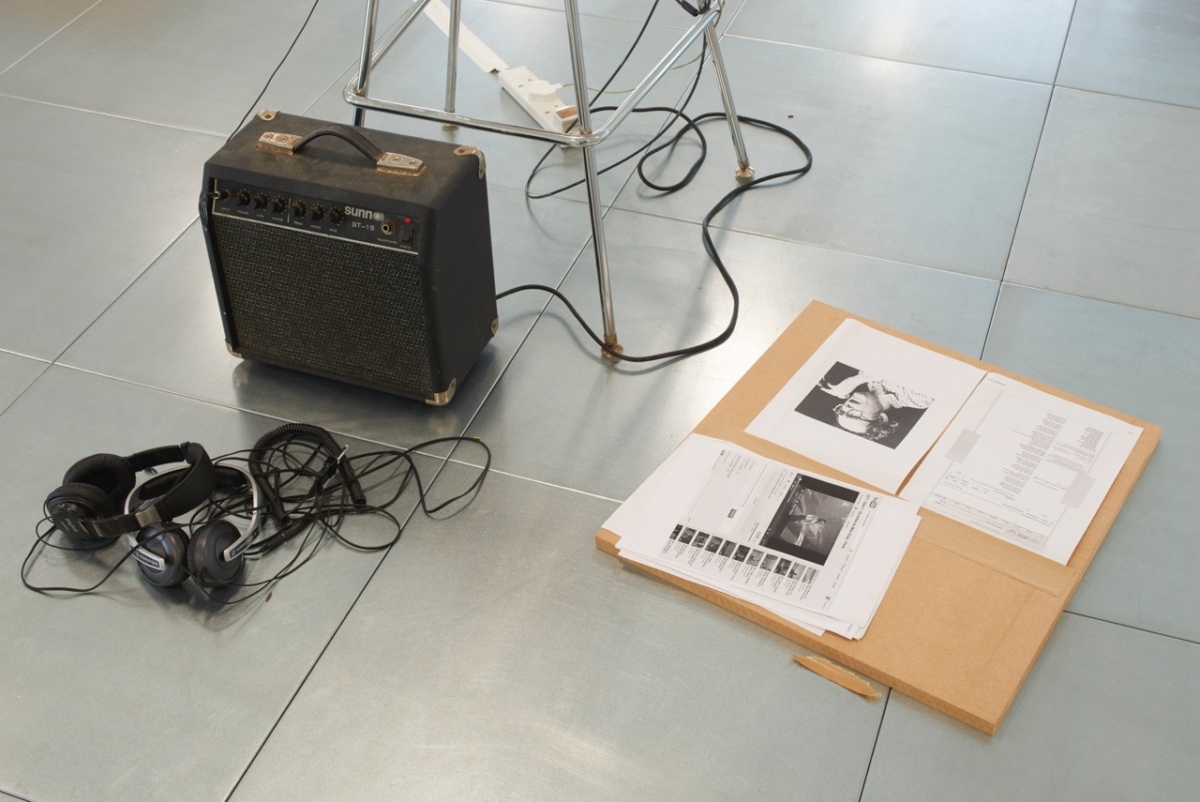

In the installation, one of the sculptural clusters looks like a disordered construction site, a visual memory from my first visit to the village, where I saw the poetic debris of everyday life, let out and about in the streets… A wooden frame placed over a shabby linoleum strip evokes both the front of a house and a large light-box, with fluorescent light illuminating a quasi-transparent instance of the brick-house. Moving to the side, there is a defaced nightstand, placed over trestles, as if waiting repair. Hanging from its open door is a double spread from the photo newspaper, with a different brick-house. Other assemblages show construction materials and photo reproductions leaning against it, a homage to the DIY skills of the villagers, that glean iconic trash of late capitalism to repair the deteriorating housing estate.

This creolisation, the hybridised appropriation of the globalised culture in a localised vocabulary of forms creates odd juxtapositions, for example, of brick chimneys with macdonalds’s logos. Is this a TAZ, a temporary autonomous zone(9)? A pirates’ encampment that resists state control? Like a rhizome, the TAZ is a node reconfiguring itself in order to enact hit and run resistances. Otherwise how to rethink today SAAL’s ideas on social emancipation?

Surviving archives

It is crucial to note here that there is no official archive of the housing estate: a main gap in the residents’ archives is the absence of the official documents that would grant them ownership of the land and houses. In this absence, their position is extremely vulnerable and the creation of such archive appears as a matter of urgency. The inclusion of three large studio trestle tables to display the records of the SAAL architecture along vernacular and personal archives is an act of reparative justice as well as a direct result of the centrality of the fpfoundation in my studio practice. The collection of found material has a very a mobile configuration “in transit and in translation” moving like Marianne Hirsch and Diana Taylor suggest happens with temporary archival forms, away from “understandings of archives as stable repositories.” (10)

Crucially, like the artists’ studios analysed by Jenny Sjöholm (11) my studio can be seen as an experimental archive in itself, with all types of collected objects being taken out and incorporated into installations set-ups, silkscreen prints, photobookzines and other practices that translate the contents of the storage boxes into new patterns that further loose its connection to its original site of production. Thus, not surprisingly, it is frequently impossible to identify the provenance of the photographs on display in any of my installations.

The inclusion of found state photo albums from the fascistic government, alongside Jose Veloso’s architectural archive and with the villagers’ personal archives in the tables query the weight of the archive to legitimise and or destabilise power positions. In the reproductions of the villagers’ photos they appear in their homes, surrounded by their collections of images and artefacts, as collectors and archivists in their own right, aware that in spite of this ordering, they lack the documents that prove their citizenship. Their staging for the camera of their personal archives reveals politically and aesthetically astute use of images, where evidence of citizen’s life is a plea for human rights. These archives of the private sphere show how politicised is the figure of the dispossessed. The image of the villagers as activists can only be complete with the memories of the films and songs that evidence their life in the public sphere, since life in the village has been wrapped up with the codes of ethno-documentary representation and the politics of image since its inception in the 1970s.

As part of the installation, I included a video archive that deals with the village in two different periods. The film Continuar a Viver -Living On (1976) was directed by Antonio Cunha Telles when the filmmaker joined the construction team in 1975. Since 1968 European militant cinema had been filming the working class struggle. Living On is both an ethnographic work and a piece of militant cinema, a politicised documentary of direct cinema, with no leading actors, rather the working class takes stage as the main character. Here, the protagonist is the fishing community performing for the camera as citizens exerting their right to the city, building their own houses collectively and assuming the control over their means of production by establishing a fishing cooperative.

The other video archive moment is a contemporary Youtube playlist of thirty cover versions of the song Indios da Meia Praia (1976). When the protest singer Zeca Afonso (1929 – 1987) wrote the soundtrack for the film he called it Indios da Meia Praia (Indigenous of the Meia Beach) as the Lagos city population called the villagers, a derogatory term that implied both foreigner and subaltern positions. The song appropriates the term to claim an anti bourgeois attitude, and it has been so popular throughout the years, that it has slowly become an anthem for the revolution. So whilst in fact many people have never visited the village, the so called Indios became a legend in its own right and the song regularly reappears as a new cover version in political rallies, TV shows and song contests.

In the site of an empty office building in the borough of Victoria, central London, the viewer’s experience of walking along the archival installation was framed by the background view out of the 6th floor window frames: outside were the red bricks tower of the neo-Byzantine style catholic Westminster cathedral erected in 1903, the dark grey cement cluster of brutalist architecture office buildings built in the mid-1970s, contrasting with the new stainless steel office buildings, a symbol of the present digital economies, with office workers visible at their computer desks. The allegorical archive could be experienced in a total environment of time-space compression at the time of globalisation.(12)

Extract from:

paula roush: Chaos of memories- Surviving archives and the ruins of history according to the found photo foundation [access full there here]

In Order and Collapse: The Lives of Archives

Editors: Gunilla Knape, Niclas Östlind, Louise Wolthers, Tyrone Martinsson,

Art & Theory Stockholm 2016

1 From an interview with the architect, video recorded in the summer of 2010.

2 Boaventura de Sousa Santos and João Arriscado Nunes, '”Introduction: Democracy, Participation and Grassroots Movements in Contemporary Portugal,” South European Society and Politics 9:2 (2004), p.11

3 Edward Ruscha, Every Building On the Sunset Strip (Los Angeles, CA: self-published, 1966)

4 Edward Ruscha, Twentysix Gasoline Stations (Alhambra, CA: The Cuningham Press,1962)

5 For a study see Ian Walker “A kind of ‘Huh?’: The siting of twentysix gasoline stations (1962)” in The Photobook: from Talbot to Ruscha and Beyond, eds. Patrizia di Bello, Colette Wilson & Shamoon Zamir (London/New York: I.B. Tauris 2012) 111 – 128.

6 As exemplified in the site-specific work of Roberth Smithson and archival accumulations of Hanne Darboven. See Craig Owens, “The Allegorical Impulse- Toward A Theory of Postmodernism, October 12 (Spring, 1980), 71.

7 James Cifford, “On Ethnographic Allegory,” cited in Catherine Russell, Experimental ethnography – The work of film in the age of video.

8 paula roush, The past persists in the present in the form of a dream (participatory architectures,archive, revolution) (London: msdm publications, 2012); first exhibited during the Brighton Photo Biennial 12 Photobook, October – November 2012 and Brighton Photo Fringe, Phoenix Brighton, November 2012

9 Hakim Bey, T. A. Z. The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism.(Brooklyn, NY: Autonomedia, 1985).See http://hermetic.com/bey/taz3.html#labelTAZ

10 Marianne Hirsch and Diana Taylor, The Archive in Transit, In On the subject of archives. See http://hemisphericinstitute.org/hemi/en/e-misferica-91/hirschtaylor 11 Jenny Sjöholm, “The Art Studio As Archive: Tracing The Geography of Artistic Potentiality, Progress and Production,” Cultural Geographies 21(3, 2014), 505– 514.

12 On the question of the national of allegory vs its globalisation using the configuration of timespace compression proposed by Fredric Jameson see Ismail Xavier, “Historical Allegory” in A Companion to Film Theory, eds. Toby Miller and Robert Stam (Malden: Blackwell, 1999) 333-334.